Red Shoes (Shulashummashtabe)

Shulashummashtabe (Red Shoes in English; Souliers Rouges in French) was a Choctaw warrior, diplomat, and trader whose actions sparked the Choctaw Civil War from 1747 to 1750.

Library of Congress

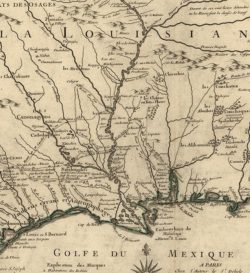

This detail from a 1718 map shows the locations of villages and towns inhabited by numerous Native American groups, including the Choctaw and Chickasaw, across parts of what is now Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida.

Shulashummashtabe, an abbreviation of Shulush-homma-mastabe, “the warrior who wears red shoes,” was a Choctaw warrior, diplomat, and trader whose actions sparked the Choctaw Civil War from 1747 to 1750. Although Shulashummashtabe was a title that many Choctaw men acquired through the late eighteenth century, this Shulashummashtabe is renowned for his roles in warfare; diplomacy with the Chickasaws, French, and British; and especially in causing internal dissension among Choctaws to erupt into civil war. He is remembered among Choctaw people and scholars today and has even served as a major character in Choctaw writer LeAnne Howe’s novel Shell Shaker.

Warrior

Born sometime around 1700 in what today is central Mississippi, Shulashummashtabe earned his title as a warrior and war leader. Success at war depended on not only physical prowess but also on the ability to manipulate spiritual power for the benefit of society. Success in hunting and war defined Choctaw masculinity at this time, enabling boys to become men by demonstrating their killing proficiency. Shulashummashtabe participated in war mainly against the Chickasaws, who used English firearms acquired via trade with colonial merchants based in Charles Town (later Charleston), South Carolina, who, in turn, sought deerskins and Native captives to enslave. Chickasaw attacks on the Choctaws started in the 1690s to seize captives and sell them as slaves to the British in South Carolina. The imperative to get revenge against the murderers and enslavers of one’s relatives kept warfare roiling between the two Native peoples.

Once the French arrived in the Lower Mississippi River Valley and along the Gulf Coast in the early eighteenth century, the Choctaws welcomed access to firearms and other trade goods to counter the English trade with the Chickasaws. The French also encouraged Choctaws to attack the Chickasaws by paying ransoms for Chickasaw scalps and heads in a series of conflicts sometimes referred to as the Chickasaw Wars. The Chickasaws also harbored groups of Natchez Indians after the Natchez revolt against the French in 1729, motivating the French to pay Choctaws to attack the Chickasaws. In 1731, for example, Shulashummashtabe led a successful raid against the Chickasaws that resulted in France recognizing his high status as a war leader. With these actions, and likely others that are not documented in French and British records, Shulashummashtabe proved his ability to manipulate spiritual power and succeed in warfare to such an extent that, according to British trader James Adair, fellow Choctaws “compared him to the sun [. . .] that enlightens and enlivens the whole system of created beings.”

Shulashummashtabe also appeared to have more than one spouse, which was not uncommon among elite Native men who demonstrated prowess in hunting, warfare, or diplomacy. One of his wives may have been Chickasaw or perhaps Chakchiuma, as those groups maintained close ties to the Western Division Choctaws, including through intermarriage. Choctaw villages and politics were divided into three main geographic areas: the Western Division villages were scattered around the upper Pearl River watershed, the Eastern Division towns were located around the upper Chickasawhay River and lower Tombigbee River watersheds, and the Six Towns were distributed along the upper Leaf River and mid-Chickasawhay River watersheds. These political divisions also had an ethnic component that meant they frequently pursued their own diplomatic and trade relationships with other peoples. Shulashummashtabe often interacted with Chickasaws despite previously having warred against them, suggesting that he may have had kinship with some of them via his Western Division kin.

Diplomat

While continuing to engage in battle throughout the 1730s and 1740s, Shulashummashtabe extended his renown by engaging in diplomacy with other Native groups and European officials. The documentary record may appear at odds, with Shulashummashtabe and his followers sometimes negotiating with French officials and other times with British representatives, sometimes attacking Chickasaws and other times meeting with them to attempt to forge a lasting peace. At different times Shulashummashtabe held medals and commissions from both France and Britain recognizing his claimed high status as they tried to manage his actions to their benefit. In 1734 he tried to establish British trade via peace with the Chickasaws, while in 1738 he apparently visited South Carolina seeking trade and the British honored him as “king of the Choctaws.” Shulashummashtabe sought advantage for his people within the relatively new system of European trade. He was not controlled by European powers or other Native peoples, and he was barely constrained by opposition from other Choctaws.

Trader

Shulashummashtabe knew that Native leaders who could consistently acquire European manufactured goods, especially guns and ammunition, via diplomacy, as payment in war, or through the deerskin fur trade could use those goods to amass loyalty from followers. Such a method for acquiring higher status was relatively new and emerged during Shulashummashtabe’s lifetime. Choctaw chiefs had long controlled the flow of high-status items, but European trade and French-British rivalry provided a different way to access foreign goods and high status. Thus when France’s trade faltered, as it did during a British naval blockade during King George’s War (1744–1748), Shulashummashtabe journeyed to Charleston and other British settlements to negotiate trade, promising protection for colonial traders and a willingness to wage war that matched British goals. British trade also suffered from disruptions, however, as well as the far distance from the Atlantic coast to Choctaw territory in today’s Mississippi. Other Native people, such as the Creeks, sometimes attacked British trade caravans and seized goods intended for Choctaws.

Civil War

The precariousness of trade and the potential status it could provide a Native person who managed its flow made for a tense and dangerous environment. Jealousies arose. Old slights and wounds demanded satisfaction. Traditional chiefs insisted on their right to make decisions about who was an ally or enemy, and competing geopolitical goals of Native and European nations remained a reality across the South. In 1743 Choctaws allied with France killed three British traders and two Chickasaw Indians. A year later King George’s War between Britain and France erupted, and in 1745 two explosive events occurred: a French officer at Fort Tombecbe sexually assaulted one of Shulashummashtabe’s wives, and Choctaw men who opposed rapprochement with the Chickasaws killed two more British traders. Shulashummashtabe and his men initiated a new diplomatic mission with the Chickasaws and responded to French and French-allied Choctaw actions by killing three Frenchmen in Choctaw country. Shulashummashtabe hoped to prevent a Choctaw Civil War and establish British trade in the Choctaw Nation by escorting a British trade caravan to Choctaw country. France demanded the head of Shulashummashtabe and submission of his followers in response to the killing of Frenchmen, leading to the assassination of Shulashummashtabe on June 23, 1747, by an unnamed Native man who was part of the trade mission being escorted to the Choctaw towns.

Shulashummashtabe’s death and French insistence that his followers be subjugated led to civil war among the Choctaws. Around eight hundred Choctaws died and three Choctaw towns were burned to the ground. European and Native witnesses of the civil war called it horrifying and “bitter beyond expression,” as the interethnic reality of the Choctaw confederation forced revenge killings across the Choctaw nation.