Teddy Roosevelt’s Bear Hunt

President Teddy Roosevelt's hunt for black bear in the northeastern Louisiana canebrakes in October 1907 was widely covered by the national media.

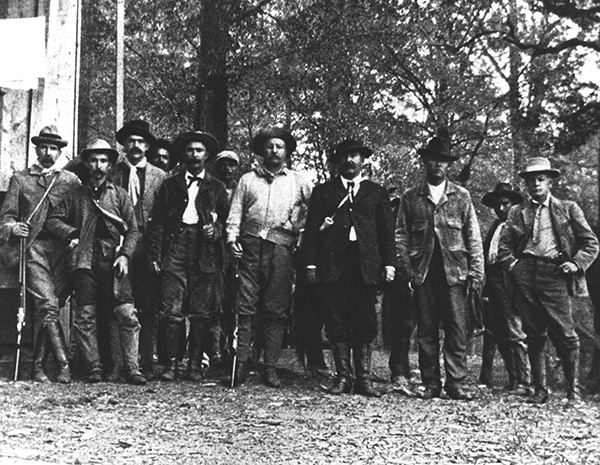

McIlhenny Company Archives, Avery Island, La.

Teddy Roosevelt's hunt for black bear in 1907 was hosted by John M. Parker and Tabasco hot sauce businessman John Avery McIlhenny. Parker would become Roosevelt's vice-presidential running mate in 1912. Pictured from left are Presley Marion Rixey, surgeon general of the U.S. Navy; John Watkins Osborn; McIlhenny; unidentified; Parker; unidentified; Roosevelt; Clive Metcalf; Jack Vesey; unidentified; and Major Amos Kent Amacker.

In addition to his presidential legacy, Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt (1858–1919) is remembered as a staunch conservationist, outdoorsman, and hunter. In October 1907, during his second presidential term, he and a group of state and national dignitaries gathered in East Carroll and Madison parishes in northeastern Louisiana for a traditional bear hunt. As revealed in his published account of the outing, Roosevelt considered the event his great adventure “in the Louisiana Canebrakes.” The hunt was Roosevelt’s second effort to bag a Louisiana black bear—one of sixteen subspecies of the American black bear—after an unsuccessful attempt in 1902 in Sharkey County, Mississippi; there Roosevelt was both ridiculed and praised in the press for refusing to shoot a bear that had been tied to a tree by his hunting guide after tracking one in the wild had proved unsuccessful. The incident prompted a New York retailer to produce “Teddy bears,” the stuffed toys that became phenomenally popular for generations of children.

Prominent Louisiana businessman John M. Parker and John Avery McIlhenny, owner of the Tabasco hot sauce enterprise, hosted the president’s 1907 hunt. Parker would become Roosevelt’s vice presidential running mate in 1912—in a failed third bid for the presidency on the Bull Moose ticket—and later served as governor of Louisiana from 1920 to 1924. McIlhenny was a member of Roosevelt’s Rough Riders in the Spanish-American War and directed the US Civil Service Commission under three presidents. Other members of the party included Dr. Alexander Lambert, the Roosevelt family physician, and Presley M. Rixey, the surgeon general of the US Navy. The chief guide for the hunt was Ben Lilly, a legendary backwoods character known for his predator-killing prowess. Bear hounds were provided by two Mississippi planters, Clive and Harley Metcalf. The dogs were tended by Holt Collier, a former slave who was credited with killing more than three thousand bears in his lifetime. It was Collier who had single-handedly captured and tied to a tree the bear that Roosevelt famously then refused to shoot during the 1902 Mississippi hunt.

After a brief stop in Lake Providence, the president’s special train pulled onto a siding at Stamboul in southern East Carroll Parish, about fifteen miles north of Tallulah on October 5, 1907. The party disembarked, mounted horses, and rode west through the uncut forest to a camp on the bank of the Tensas River. Roosevelt was enthralled with the vast virgin swamp and wrote of the giant trees and abundant wildlife. To his son Kermit, he wrote, “It is a wild country all right, for today across the bayou we suddenly caught a glimpse of two wolves which came down to the water to get a drink.” The bears, however, did not cooperate. The hunters found signs of bears, and the dogs managed to track and jump several, but the president never got a shot. After a week of unrewarding effort, other than a deer killed for camp meat, Roosevelt began to grumble that maybe they were in the wrong location. Lilly agreed, and the hunters moved about fifteen miles south to Bear Lake in Madison Parish. Of this location, the president recorded, “Our present camp is in a lovely place, beside a long, narrow lake, or bayou, which is beautiful just at this moment under the moonlight, great cypress trees standing along the bank like sentinels above the rest of the forest.”

From the new camp, the hunters pursued their quarry persistently. The dogs found bears, but their quarry quickly sought refuge in the impenetrable canebrakes, confounding both hounds and hunters. After several days, as the end of the hunt approached, the party decided to change tactics. Instead of the president waiting on a crossing stand for the dogs to drive a bear to him, he would attempt to ride with the pack in hopes of getting a shot at the fleeing animal. The next morning, the plan worked: the dogs jumped a bear and Roosevelt made a desperate, dangerous gallop through the swamp to head them off. He later wrote, “The tough wood horses kept their feet like cats as they leaped logs, plunged through bushes, and dodged in and out among the tree trunks; and we had all we could do to prevent the vines from lifting us out of the saddle, while the thorns tore our hands and faces.” After the evening campfire, where the day’s hunt was rehashed, the president once again wrote Kermit of the adventure:

“At last today I killed my big she bear—202 lbs. It was my thirteenth day; now everything is pure pleasure. The dogs had her up for nearly three hours, while we galloped on horseback and ran on foot up and down the outside of the dense canebrakes in which the chase took place, at different times all of us were thrown out. At last one of these planters—very fine fellows—and I heard the bay in a dense canebrake, and slipped in; finally as we crouched motionless the bear walked near enough for me to see her through the cane. She was twenty yards off. I shot her through the lungs at first shot, and then broke her back between the shoulders lest she should injure the leading dog. The hunt was great fun.”

After a day of rest, the hunters broke camp and Roosevelt rode back to his waiting train. On the way, he visited a nearby plantation owned by Mr. and Mrs. Leo Shields. During the visit, Mr. Shields mentioned the need for a local post office. The president agreed to look into the matter and departed on October 21. Months later, a new post office was established at Stamboul, which was promptly renamed Roosevelt.

Theodore Roosevelt’s Louisiana bear hunt was widely reported in the national media. The legacy of the visit often overshadows his more enduring contributions to the conservation of Louisiana’s natural resources. He was responsible for creating an assemblage of lands that became the National Wildlife Refuge System. Several of the twenty-four refuges comprising more than 568,000 acres in Louisiana now provide critical habitat for the threatened Louisiana black bear.