Knights of the White Camellia

The white supremacist group Knights of the White Camellia emerged during Reconstruction, and were referred to as Louisiana's version of the Ku Klux Klan.

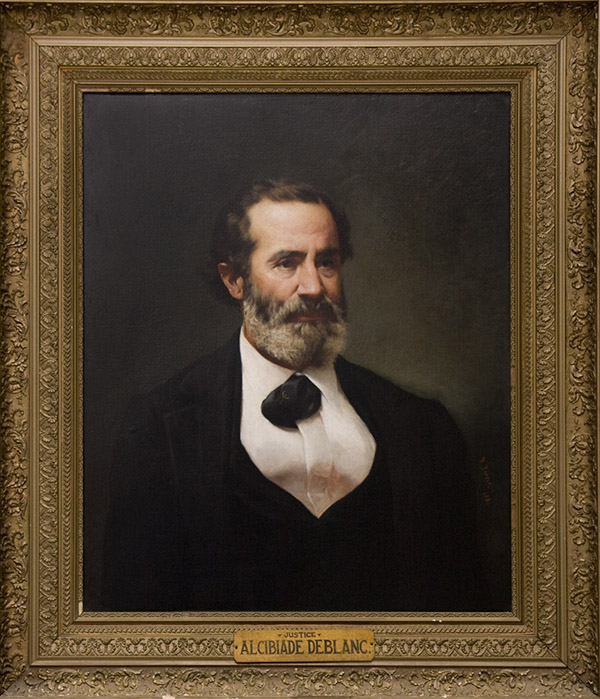

Courtesy of The Law Library of Louisiana

Alcibiades DeBlanc. Poincy, Paul (artist)

Often referred to as Louisiana’s version of the Ku Klux Klan, the Knights of the White Camellia emerged during Reconstruction as a force to combat the social and political changes wrought by the “radical” state constitution of 1868. Despite the organization’s short life span and ultimate failure, its deeds influenced the governing strategy of both national and state Republicans as well as the methods by which Democratic conservatives ultimately overthrew Reconstruction.

As it did in other Southern states, the US Congress’s passage of the Reconstruction Acts in 1867 mandated the formation of a new government in Louisiana. The move deeply demoralized the political will of those Democratic conservatives whom the legislation had ejected from power while simultaneously energizing state Republicans, who quickly moved to establish a new government. By March 1868, a biracial convention had written a new state constitution. The next month, Louisiana’s voters ratified the constitution and elected Henry Clay Warmoth, an Illinois-born Republican, as governor. Well ahead of its time, the Louisiana state constitution of 1868 featured a sweeping civil rights code and dramatically altered the balance of political power in the state. For the first time in Louisiana’s history, black men had not only voted in an official state election, a significant number now held office.

Formation of the Knights of the White Camellia

Though they looked on with dismay, conservative Democrats invested little effort in opposing the creation of the new state government along Republican lines. Many Democrats simply considered the process illegitimate, and they believed that the entire Radical Reconstruction program could be crushed by a successful campaign to elect a Democratic presidential ticket in the coming November. Thus, the Knights of the White Camellia emerged during the spring of 1868 primarily to campaign in Louisiana for the Democratic presidential ticket of Horatio Seymour and Frank Blair.

Most sources agree that the Knights of the White Camellia first appeared in St. Martin Parish under the leadership of Alcibiades DeBlanc, a lawyer and former Confederate general. The degree to which the organization achieved any sort of uniformity may never be known, but it did have bylaws. Word of its existence likely spread through the existing network of political clubs that were common in rural nineteenth-century America. It is certain, however, that by the summer of 1868, the movement had spread across much of Louisiana. It featured a hierarchy of circles, and “chiefs of circles” who reported on activities to superiors. Yet, if the deeds of the Knights of the White Camellia are any indication, the groups’ leaders had relatively little control over its rank-and-file members. While the Knights of the White Camellia (KWC) do not seem to have been active in New Orleans, political organizations such as the Crescent City Democratic Club seem to have filled an identical role in the upcoming election.

Activities

The Knights’ primary weapon was intimidation, which could take many forms. Members later gave testimony during a congressional investigation that seemed to substantiate claims that KWC members, unlike the Ku Klux Klan, did not go about robed and disguised. That freedmen recognized their tormentors only heightened the effect. Their activities included armed patrols on roads at night, during which they periodically confronted freedmen and white Republicans with violence, some of which was lethal. Some of the group’s worst outrages came at the hands of small parties of men who used the organization to settle personal animosities. More common, however, were the sort of intimidation tactics that in the coming decades would be as familiar to segregationists in the South as they would to union-busting factory owners in the North. The Knights wanted the freedmen to recognize them as the sort of influential men who could hurt them financially as well as physically. One member, who distributed “certificates” to black men seen voting the Democratic ticket, indicated that the Knights wanted to make sure that they were “friendly to those who had befriended us.” Thus, as early as 1868, conservative white Southerners recognized that their political future hinged upon their ability to either suppress or control the black vote.

Influences on Politics of Reconstruction

The intimidation tactics of the KWC and similarly predisposed clubs in New Orleans proved effective in the election of 1868. Although Republicans had turned out in large numbers the previous April to elect its governor, they stayed home in November. As a result, Democrats carried Louisiana for Seymour and Blair by a wide margin. Yet the overall plan to overthrow Reconstruction nationally had failed. The only other former Confederate state to give its electoral votes to the Democratic Party was Georgia, where a similar terror campaign by the Klan had kept Republicans from the polls. In the North, a majority voted for Ulysses S. Grant, though his landslide in the Electoral College obscures the closeness of the 53/47 percent margin in the popular vote. The overarching strategy of the KWC had fallen short, but not by much.

The Republican Party, both nationally and in Louisiana, heeded the lessons of the turbulent 1868 election. Nationally, the Enforcement Acts made the sort of Klan-style violence and intimidation tactics perpetrated by the KWC a federal crime. Known popularly as the “Ku Klux Act,” it proved to be somewhat effective until gutted legally by United States v. Cruikshank (1876), a US Supreme Court case stemming from a violent episode in Grant Parish known as the Colfax Massacre. In Louisiana, Governor Warmoth sought out a more tangible solution to ensure the safety of his party, forming both the Louisiana State Militia and the much more effective and heavily armed Metropolitan Police.

The Democratic White League that emerged in the spring of 1874 also owed much of its success to lessons learned in 1868, since many of the same men who had belonged to the KWC helped form the White League. Shifting national attitudes away from the merits of Reconstruction combined with the more politically savvy tactics of the White League ultimately played a key role in the overthrow of Republican rule in Louisiana in 1877.