Prehistoric Archaeology in Louisiana

This entry explores the history of American Indian life in Louisiana from 11,500 BCE to 1700 CE through the study of prehistoric archaeology.

LSU Press

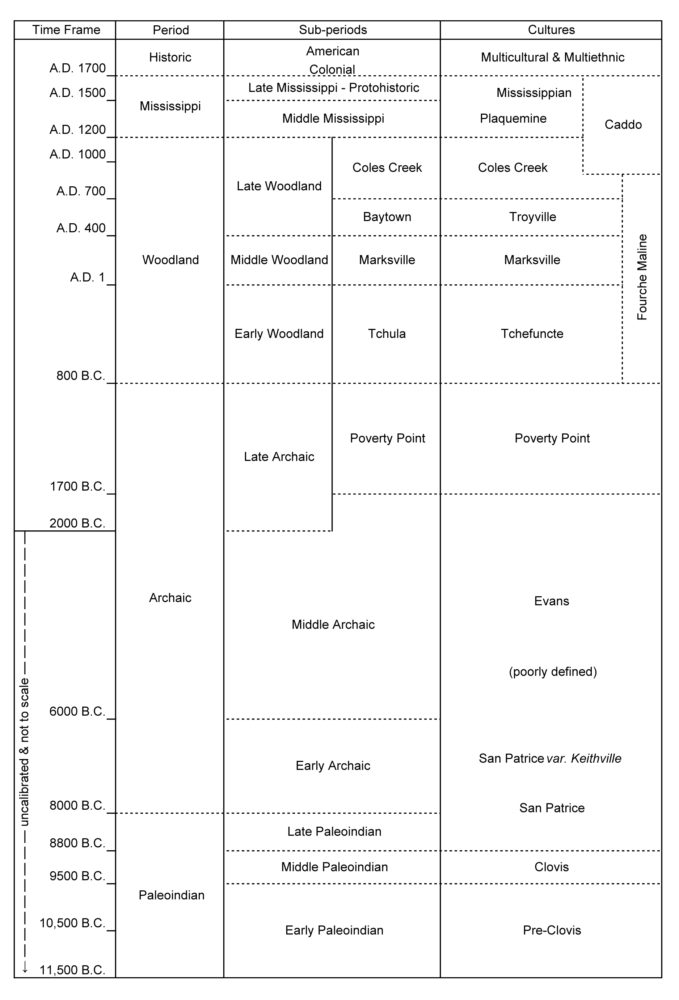

Culture chronology chart from Mark A. Rees's Archaeology of Louisiana published by LSU Press

Archaeology is the study of people in the past. Using the meager remains of broken tools, mounds of earth, and soil colors and textures, archaeology provides rich, tangible information about early people whose histories are not recorded in written records. The stories of American Indian life in Louisiana from 11,500 BCE to 1700 CE are available through the study of prehistoric archaeology. Historical archaeology, the focus of another essay, corrects and augments records of later people who lived in Louisiana after 1700 CE.

Overview

The diverse cultures present when Europeans arrived in Louisiana had ancient roots. Stone spear points, called Clovis points, indicate that American Indians were in Louisiana at least as early as 11,500 BCE, when Pleistocene megafauna (literally “large animals”), including mastodons, were commonplace. As the last Ice Age ended and the climate warmed, American Indians adapted to changing natural and social landscapes. These adaptations are evidenced by changes in tools like projectile points and pottery; in the styles of artwork that adorned everything from everyday cooking pots to exotic artifacts signaling rank and privilege; and in the shape and size of earthworks left behind. For instance, spears eventually gave way to the bow and arrow. Although they traded for pottery well before this, Louisianans had developed their own distinctive pottery vessels by 800 BCE. Long-distance trade in exotic stone and other items flourished during some periods, and declined in others. Political and religious systems also waxed and waned, and are visible to archaeologists in everything from the symbolism in pottery decorations to the sizes and shapes of ceremonial centers.

General descriptions of the types of cultures that lived in Louisiana during archaeologically defined time periods are presented in this essay. Here, the focus is on the types of tools used, foods hunted and gathered, and basic social organization. At this general level, archaeologists divide Louisiana’s past into the same broad time periods that are applied to precolonial American Indian cultures throughout the eastern United States. It is important to note that the beginning and ending dates of periods and cultures are not as abrupt as they appear in this scheme. The divisions are just tools archaeologists use to communicate with each other. The time periods are: Paleoindian (11,500–8000 BCE), Archaic (8000–800 BCE), Woodland (800 BCE–1200 CE), and Mississippi (1200–1700 CE). Although the Hernando de Soto expedition (1539–1543) and the LaSalle expedition (1682) had some limited contact with Louisiana Indians along the Mississippi River, archaeologists generally divide the prehistoric from the historic at 1700, when French colonization began. With more sustained contact after 1700, there is a rich written and pictorial record that fleshes out the historical archaeology record.

Each of the precolonial time periods is divided into Early, Middle, and Late sub-periods, and multiple cultures might be recognized within each sub-period (see culture chronology chart). Cultural divisions are derived from a number of factors, but changes in artifact styles are the basis for most. Broad distinctions can be made from changes in stone point styles. However, once pottery was adopted, the lively decorations placed on vessel exteriors allow for finer discrimination of discrete cultures, and provide valuable information on trade, alliances, and influences. Cultures of the distant past are named by archaeologists, usually after a river or other natural or cultural feature in the area where sites are found. Tribal names are only known after European contact, and many of these names are not what the people called themselves.

Paleoindian Period 11,500–8000 BCE (Pre-Clovis, Clovis, San Patrice Cultures)

The Paleoindian period in Louisiana includes the cultures that existed at the end of the Pleistocene epoch (11,500 BCE) until the beginning of the Holocene (8000 BCE). Early in this period, plants and animals, as well as shorelines and river courses, were quite different than they are today. Subsequently, Paleoindian cultures experienced rapid climate change and dramatic sea-level rise. The San Patrice culture straddles the end of the Paleoindian period and the beginning of the Archaic, when more modern climatic conditions prevailed.

Early Paleoindian 11,500–9500 BCE (Pre-Clovis Culture)

Until recently, the Clovis culture was considered the earliest in the Western Hemisphere, but that has changed. It is now widely accepted that there were people in the Americas earlier than the Clovis culture. How much earlier remains extremely controversial, and pre-Clovis culture is not well-defined. However, information from a site in Texas indicates pre-Clovis peoples were surprisingly similar to later Paleoindian cultures. Pre-Clovis sites have been located in many New World areas, from Pennsylvania to southern Chile, but none have been identified in Louisiana, probably because our active landscape has buried or drowned evidence of these earliest inhabitants.

Middle Paleoindian 9500–8800 BCE (Clovis Culture)

While the Clovis point is no longer considered the earliest spear point in the Western Hemisphere, it retains its distinction as one of the most technically difficult and aesthetically pleasing projectile points produced during any time period. The points were fastened onto long spears and used in the hunting and butchering of Pleistocene megafauna. These huge beasts were once considered the most important component of the Paleoindian diet. Since herds of these animals traveled throughout the year, archaeologists thought Clovis peoples did too. This widespread travel was thought to account for the similarity of Clovis points found throughout the United States. It now appears that Clovis people were more sedentary and had a diverse diet, which included smaller mammals and reptiles like turtle, along with fish, shellfish, and a wide variety of plants. Some sites, especially those near high-quality stone outcroppings, had either long-term habitations or were visited repeatedly over long periods of time.

Virtually nothing can be said with confidence about the social organization of Middle Paleoindian groups in Louisiana, although most archaeologists suggest some kind of band-level organization. Bands, consisting of some thirty to fifty individuals, are considered egalitarian, with status defined only by age and gender. Most Clovis points recovered in Louisiana are isolated finds—there were no other artifacts or evidence of human activity where the Clovis points were found. Only a very few Clovis sites have been identified in Louisiana.

Late Paleoindian 8800–8000 BCE (San Patrice Culture)

During the Late Paleoindian period, more modern climatic conditions were developing. While large spear points continued to be made, smaller points became the norm. Projectile point styles, while still similar over large areas, do show some regional variation, which indicates either that people did not interact closely enough to learn the same styles, or that groups wanted to differentiate themselves by making different point styles. San Patrice points share some of the technological aspects of Clovis and related points, but their smaller size suggests they might have been used with lightweight spears cast with atlatls, or throwing sticks, which were present in the subsequent Archaic period. Again, small bands with rank determined only by age and gender are considered to have been the social norm.

Archaic Period 8000–800 BCE (San Patrice, Evans, Poverty Point Cultures)

The long Archaic period encompasses adaptations to major environmental shifts as the last Ice Age ended and the landscape changed. People adapted to rapid sea-level rise, which had significant effects far beyond the coast, and to major shifts in wildlife and vegetation.

Early Archaic 8000–6000 BCE (San Patrice Culture)

Continuing the trend begun in the Late Paleoindian period, in the Early Archaic, large leaf-shaped stone points gave way to smaller points, which were attached onto lighter spear shafts and propelled with atlatls, or throwing sticks. Stone points became smaller and, over time, the familiar tree-shaped (stemmed) point appeared. Tools like axes and grinding stones were more common than in the Paleoindian period, and may reflect the inclusion of more nuts, seeds, and grains in the diet. As in the Paleoindian period, social organization is presumed to have been at the band level.

Middle Archaic 6000–2000 BCE (Evans Culture)

The Middle Archaic was a time of innovation in both technology and society. By this time, sea level was high enough to slow river flow, and a reliance on riverine foods evolved. This change in resource use may be reflected in changes in cooking and hunting techniques. The first fired earth objects (i.e., “clay cooking balls”) appeared. The earliest of these were cube-shaped and used for cooking and perhaps for heating stone to make it easier to work into tools. Spear points were routinely notched (indentations were made to aid in lashing the point to a spear); Evans and Sinner points stand out by having multiple notches. Although band-level societies were probably still the norm, something on the social landscape changed, because this is the period when mounds first appear. The Middle Archaic mounds in Louisiana are the oldest in North America. While some of the mound sites, like the LSU Campus Indian Mounds, are relatively small, others, such as Watson Brake, are large, and represent considerable effort in planning and execution. Archaeologists disagree over whether such complicated, long-term construction projects required some form of status-related leadership positions (however temporary) or whether the earthworks could have been built simply by consensus among the egalitarian builders. While Watson Brake may have had a permanent population, other early mound sites are considered to have been sacred places where isolated bands came together periodically to worship, dance, sing, feast, and to find mates. Perhaps not coincidentally, a new artifact, the effigy bead, appeared at this time. Mound building ceased by 2800 BCE, and did not resume in Louisiana for about a thousand years.

Late Archaic 2000–800 BCE (Poverty Point and Other Late Archaic Cultures)

During the Late Archaic period, most people in Louisiana continued to live more or less like their Middle Archaic predecessors in terms of tools, diet, and social organization. Indeed, more mound sites were built in the Middle Archaic than in the Late Archaic. However, on a long, high ridge just west of the Mississippi River floodplain in northeast Louisiana, the Poverty Point site was built. The site is so significant that it became the 1,001st World Heritage property listed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 2014. Massive earthworks were constructed and extensive trade in exotic goods brought tons of high-quality stone and other items to the site from as far away as Iowa and Florida. Pottery, most of it imported, appeared first in Louisiana at Poverty Point. Even basic utilitarian items such as fired earth objects were created in special, whimsical forms. The site was occupied from about 1700 to 1100 BCE, when it was abandoned, for reasons as murky as the causes of its creation. However, few sites have been found in the Lower Mississippi River Valley in the interim between the end of Poverty Point and the beginning of the Tchefuncte culture around 800 BCE. Some suspect widespread and persistent flooding caused abandonment of the area for some time.

Woodland Period 800 BCE–1200 CE (Tchefuncte, Marksville, Troyville, Coles Creek, Caddo Cultures)

The Woodland period was originally defined as a time when increasingly sedentary societies became adapted to the post-Pleistocene Woodland environment. Living year-round in one place allowed groups to adopt new tools—like pottery—and new foods, as native plants were domesticated (instead of opportunistically gathered). Population increased. Stable, relatively dense populations required new forms of social organization, and so societies became somewhat more hierarchical. As more data accrue, it is clear that there are numerous deviations from this model, but it still provides a basis for discussion.

Early Woodland 800 BCE–1 CE (Tchefuncte Culture)

Throughout most of the eastern United States, the Early Woodland period coincides with the widespread appearance of pottery. In Louisiana, the earliest abundant, locally made pottery is called Tchefuncte (“tchefuncte” is a Choctaw word for chinquapin). Pottery appeared in small quantities around 1100 BCE, and became widespread by 800 BCE. Vessel forms and the designs on the vessel surfaces are similar to those created by other cultures from Mississippi to Florida, indicating considerable communication across the lower Southeast. Limited trade in exotic items occurred, but the trading networks were less vast than when Poverty Point culture flourished. The atlatl was still used; some Early Woodland points can be distinguished from points made during the Late Archaic, but others are indistinguishable. Elsewhere in the eastern United States, it is clear that people were domesticating native plants like sunflower, goosefoot, and amaranth, but there is no evidence for domestication in Louisiana. Despite the fact that pottery designs were shared with other cultures, Early Woodland peoples in Louisiana are generally considered somewhat isolated. However, sometime around the turn of the millennium, Early Woodland people began to be influenced by a culture centered in the Ohio and Illinois River valleys—the Hopewell culture.

Middle Woodland 1–400 CE (Marksville Culture)

During the Middle Woodland period, Hopewell influences spread throughout Louisiana. Changes in burial practices and pottery styles were established by around 1 CE. Trade in exotic goods expanded. While at Poverty Point there is no indication that exotic goods were related to status, many of the Middle Woodland artifacts may indicate some kind of social hierarchy. Mortuary ritual included building domed mounds to cover the dead. And, while some burial mounds were used for an entire community, a very few others contained tombs reserved for certain sets of individuals—another indication of a status hierarchy. Instead of social divisions based solely on age and gender, there may have been an important clan or lineage whose members required special treatment after death.

That said, Hopewell influence was attenuated in Louisiana. The number of exotic goods and the number of sites with burial mounds is quite small compared to other areas in the Hopewell network. And, while Hopewell people in Illinois and Ohio were heavily invested in cultivating native plants, people in Louisiana continued their long tradition of fishing, hunting, and gathering wild foods. Hopewell influence was also short-lived, probably lasting no longer than a couple of generations. Northern influence petered out between 200 and 400 CE. For most, lifeways at the end of the Middle Woodland was similar to that established long before.

Late Woodland 400–1200 CE (Troyville, Coles Creek, Caddo Cultures)

Once considered a period with few remarkable developments, the Late Woodland in Louisiana is now seen as a time of innovation and change. Despite its improved reputation, however, the Late Woodland remains poorly understood. The basic components of the diet remained the same—most Louisianans continued to eschew plant domestication—but hunting techniques (and possibly warfare) changed dramatically as the atlatl and spear gave way to the bow and arrow. Projectile points, actual arrowheads, were smaller and more aerodynamic. Designs on pottery indicate increased communication with groups across a multi-state area.

Dome-shaped burial mounds continued to be built, but other mounds were flat-topped. Initially, flat-topped mounds may have functioned like theater stages, but through time they became bases for buildings, temples, houses, and other structures that surrounded small formal plazas. By the end of the period, mounds supported temples and houses of a developing elite class whose status was inherited. A few, very large ceremonial centers were present, and there may have been hierarchies of sites in some regions.

In one or two sites that were occupied near the very end of this period, kernels of corn appear. Corn was domesticated in Mesoamerica almost ten thousand years ago. From there, it slowly dispersed through the Southwest and, by pathways not well understood, into the Lower Mississippi River Valley. The Caddo in northwest Louisiana adopted corn agriculture relatively early, by 900 CE. However, with a few exceptions, corn and other domesticated crops were absent elsewhere in Louisiana during the Woodland period.

Mississippi Period 1200–1700 CE (Plaquemine, Mississippian, Caddo Cultures)

During the Mississippi period in the southeastern United States, many people made pottery with crushed shell in the clay paste, and the vessels often bore a distinctive set of incised designs. The people of this period were dependent on maize agriculture, and in some areas, they built massive ceremonial sites which were overseen by chiefs who had significantly more power than leaders in preceding periods. The power of chiefs and principal men was reflected in their houses, which were built on flat-topped mounds, and in their possession of elaborate prestige goods that signaled rank. Chiefs and other principal people were buried with lavish displays of these goods. These innovations, which are traits of the Mississippian culture, originated at Cahokia in the St. Louis area by about 1050 CE and subsequently spread unevenly across the East and Midwest. One conduit for the spread was down the Mississippi River, and northern influences were first felt in northeast Louisiana around 1200 CE. Another wave of influence came from the east and into the delta parishes. Neither penetrated very far. As in the past, Louisianans responded to region-wide waves of political-religious ideas by adopting what appealed to them but keeping much of their traditional culture intact.

Middle Mississippi 1200–1500 CE (Plaquemine, Mississippian, Caddo Cultures)

Beginning around 1200 CE or so, some cultures in Louisiana adopted a few Mississippian traits, while maintaining a “local” trajectory. They built larger ceremonial centers, especially in northern Louisiana, and they experimented with agriculture. In some areas, chiefs and their relatives had houses constructed on the surface of platform mounds at ceremonial centers. Other aspects of Mississippian culture in Louisiana include exotic and locally made artifacts (like pottery) with designs indicative of the widespread Mississippian culture cosmology. People from high-status lineages were accorded special mortuary treatment. However, the magnitude of power and privilege within the chiefly lineages apparent at the larger Mississippian centers elsewhere did not exist here. As in the past, most of the population lived in isolated hamlets, where they may have farmed corn, beans, and squash. Nevertheless, they still relied heavily on the fishing, hunting, and gathering traditions of old.

Late Mississippi 1500–1700 CE (Plaquemine, Mississippian, Caddo Cultures)

Between 1400–1500 CE, many of the largest chiefdoms in the Southeast were failing. Some of the most heavily populated areas were abandoned as Mississippian societies were redefined and reorganized. Other large sites lost their preeminent positions. For instance, the huge Middle Mississippian Emerald Mound and village site near Stanton, Mississippi, was superseded as the principal seat of power by the Grand Village of the Natchez. Mound building was still occurring at the Grand Village in the early 1700s.

It was these recently reorganized societies that met Europeans, first the Spanish of the de Soto expedition (1539–1543) and then, beginning in 1682 with the LaSalle expedition, the French. French colonization began in 1699, with the arrival of Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville. It is clear from the early documentary record that many American Indians thought these strangers and their odd ideas could be dealt with as they had dealt with new ideas in the past—accepting some things, especially prized and practical trade items, but rejecting complete conversion to alien ideas. In some areas, this strategy worked. In others, particularly those ravaged by disease, it failed. Many tribal names recorded in the initial years of French colonization disappeared just decades after contact. Oral histories and the archaeological record remain to tell their story.