Insurrection of 1768

In 1768, French creole merchants and planters rebelled against the imposition of Spanish rule.

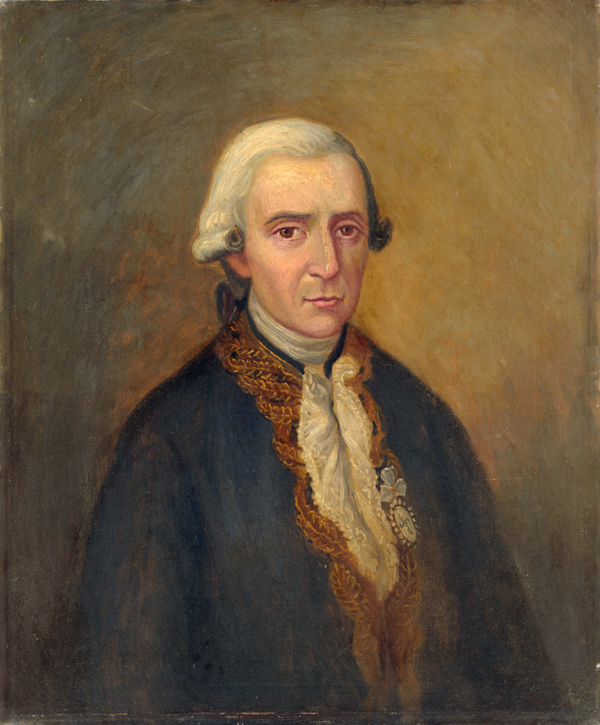

Courtesy of Louisiana State Museum

Governor Antonio de Ulloa. Molinary, Andres (Artist)

The Insurrection of 1768 constituted a rebellion against colonial Louisiana’s first Spanish governor, Antonio de Ulloa, and a temporary victory for New Orleans’s elite French Creoles. The revolt occurred after the 1763 Treaty of Paris ended the French and Indian War (1754–1763) and divided the territories of French colonial Louisiana between Spain and England. Events surrounding the insurrection revealed long-standing problems with the colonial government of French Louisiana and the initial weaknesses of Spain’s occupation policy. Spanish forces would ultimately resolve the conflict in 1769 and control Louisiana west of the Mississippi River for the remainder of the century.

By the 1760s, power in the colonial government of French Louisiana was effectively divided among the governor, the commissaire-ordonnateur, and the Superior Council. A state of permanent political rivalry existed between the governor and ordonnateur, which meant that the Superior Council, and particularly the attorney general, gained a reputation for relative stability in an otherwise dysfunctional system of governance. In this confusing political climate, Denis-Nicolas Foucault, the ordonnateur of Canadian descent, and Charles-Philippe Aubry, the governor of French descent, competed for the loyalty of a powerful group of French Creole merchants and planters with considerable influence over the Superior Council. Nicolas Chauvin de Lafrénière, the attorney general and chief power broker in the Superior Council, was a first-generation son of French Louisiana’s Creole oligarchy and the person most responsible for the Insurrection of 1768.

Antonio de Ulloa arrived at New Orleans in March 1766, though he failed to proclaim Spanish sovereignty over Louisiana and allowed the French flag to remain flying over the Place d’Armes. The actions of Ulloa confused the Creole inhabitants of Louisiana and basically left the administration of government to Aubry, Foucault, and Lafrénière. That being said, Ulloa recognized the judicial and legislative power of the Superior Council as a direct threat to his gubernatorial authority. Ulloa’s fears were realized in September 1766 when Foucault, Lafrénière, and other members of the Superior Council sided with Creole merchants against the implementation of Spain’s rigid trade restrictions. Aubry, on the other hand, sympathized with Ulloa’s predicament and functioned as a puppet governor after Ulloa conducted the transfer of sovereignty ceremony at the Balize post in 1767. Afterwards, Louisiana’s economy continued to suffer while Foucault and Lafrénière jockeyed for public support against Aubry’s cooperation with the absent Spanish governor.

Opposition to Spanish rule reached a tipping point when Ulloa issued a second set of trade regulations in October 1768 that put restrictions on the customary commercial practices of French Louisiana. French Creoles affiliated with the Superior Council, many of whom stood to lose profits because of Spain’s system of mercantilism, spread rumors about Ulloa’s supposed plan to oppress French, Acadian, and German settlers. Members of the Superior Council’s inner circle, including Foucault and Lafrénière, also circulated a petition throughout New Orleans calling for the immediate expulsion of Ulloa and all Spaniards from Louisiana. On the morning of October 29, 1768, all but Foucault (as was customary, the ordonnateur deferred to the collective decision of the council) voted for banishment, with Lafrénière having made an impassioned argument for the rights of colonists and against the tyranny of Ulloa’s regime.

Ulloa left New Orleans on November 1, 1768, and accused Foucault, Lafrénière, and practically the entire Creole oligarchy of treason. Foucault and Aubry promptly sent reports to the Spanish Crown depicting their own versions of the coup d’état. The Spanish Crown, with the support of the French King Louis XV, commissioned General Alejandro O’Reilly to suppress the rebellion with a force of 2,000 men and more than twenty ships. After consulting O’Reilly and his emissary Francisco Bouligny, Lafrénière urged the inhabitants of New Orleans to accept the authority of the Spanish regime and avoid military engagement. O’Reilly arrived at New Orleans on August 18, 1769, and took possession of the city without bloodshed. With the aid of Aubry, O’Reilly arrested Lafrénière and twelve of his coconspirators. Foucault avoided prosecution but was nonetheless deported on October 14, 1769. Lafrénière and four of his chief coconspirators were executed by firing squad on October 25, 1769, while the remaining arrested insurrectionists received prison sentences. O’Reilly pardoned the petits gens (soldiers, artisans, laborers, sailors, small businesspeople) of the city for their involvement in the rebellion.

Several governmental reforms followed the suppression of the Insurrection of 1768. First, O’Reilly dissolved the Superior Council and established a cabildo (Spanish city council) in its place. Second, he invited Native American leaders to New Orleans in order to ceremonially introduce them to the new Spanish regime and initiate trade and military alliances. Third, he instituted trade restrictions that made Havana, Cuba, the chief entrepôt for Spanish and French merchants who conducted business in New Orleans. Fourth, he oversaw the inspection of the colony outside of New Orleans that resulted in the recognition of eleven posts stretching from present-day Ascension Parish to St. Louis, Missouri. With these tasks completed, O’Reilly departed from New Orleans in February 1770, thus leaving Luís de Unzaga as governor of a colony that was now a dependency of Cuba.

Almost forty years after the insurrection, at the beginning of US rule in Louisiana, a Creole elite reasserting their Gallic identity would lionize the rebels of 1768 as patriotic French martyrs by naming the alleged site of their execution in New Orleans “Frenchmen Street”; the street still retains the name.