Hurricanes in Louisiana

Louisiana hurricanes have played an essential role in the state’s history from colonization through the present and are as memorable as the places and people they impact.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

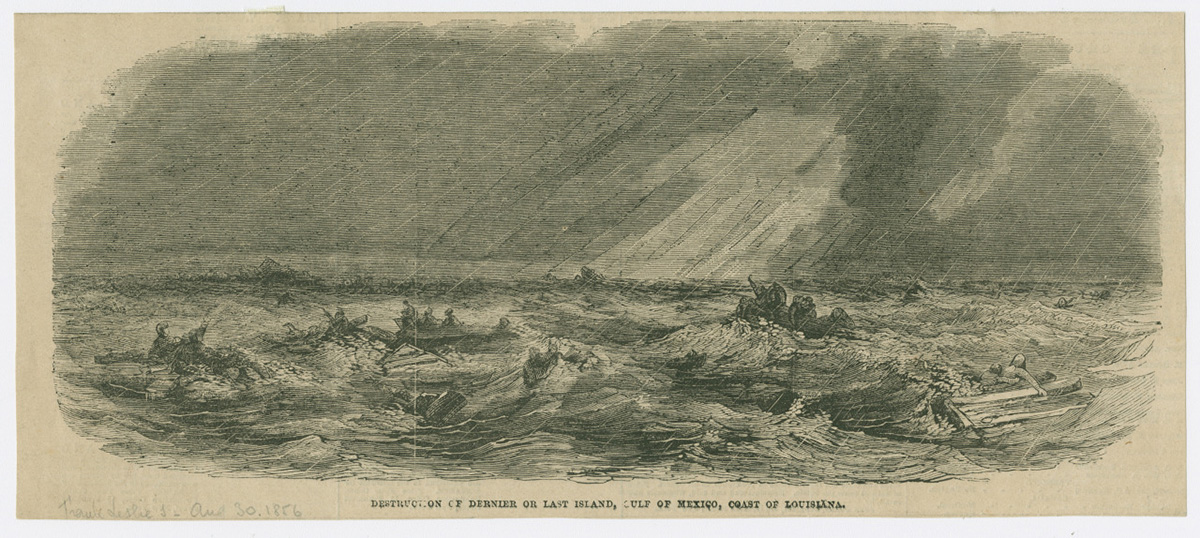

"Destruction of Dernier or Last Island" as depicted in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 1856.

Hurricanes are a fact of life in Louisiana. Each year, from June through November (and sometimes outside this time frame), Louisianans look anxiously toward the Gulf of Mexico, awaiting their arrival, wondering if an upcoming storm will be the next “Big One.” Because hurricanes impact the state almost every year, their regularity marks Louisiana lives, influencing and frequently changing the state’s people, history, culture, economics, infrastructure, and government, often in dramatic ways. Hurricanes have played an essential role in Louisiana’s history from colonization through the present and are as memorable as the places and people they impact.

Early Louisiana Hurricanes, 1500s–1700s

Limited evidence exists about the experience of Louisiana’s Indigenous peoples with hurricanes prior to European contact, but Native Americans were familiar with these storms and used them to guide decisions about where to live. European explorers to the Gulf of Mexico wrote fervently about the storms they experienced. By 1555 the word huracán—sometimes spelled herycano, furicano, huricano, or heuricane before assuming its present form “hurricane”—had appeared in letters, reports, books, and other written works in many European languages to refer to the violent storms one could experience in the Americas.

The first recorded hurricane to hit Louisiana made landfall at the mouth of the Mississippi River on October 23, 1527. We know of its existence through records left behind by Spaniard Cabeza de Vaca, whose account of Pánfilo de Narváez’s expedition included a description of the storm Narváez and his men encountered while sailing past the mouth of the river. The storm caught them off guard, “tossed them like driftwood,” destroyed two ships, and killed sixty to seventy men.

After the French began to settle in Louisiana in 1699, French colonizers recorded hurricanes that struck the Mobile settlement in 1711 and 1717 and New Orleans in 1722. The 1722 hurricane, which hit the new capital of New Orleans, was particularly devastating. The hastily constructed buildings of New Orleans were no match for the fifteen hours of winds impacting the region. According to Pierre François Xavier de Charlevoix, “To crown the misfortunes” of the new settlement, which was already struggling due to financial challenges, the hurricane destroyed completely “the church, hospital, and thirty houses or log huts […]; all the other edifices were injured.” This ultimately left “two-thirds of the buildings in need of ‘complete rebuilding’” and impacted the city’s development. Ships in the harbor, three small boats filled with supplies, and a significant number of prospective crops were also lost, despite efforts by then-Governor Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville and his men to prepare for the storm.

Accounts of hurricanes, like that of the 1722 storm, made potential settlers wary of Louisiana, especially as the storms often influenced both the passage to Louisiana and the settlement of it. Between 1722 and 1800, at least thirteen more storms struck the colony, often bringing devastation to fledgling crops, settlements, and lives. So regular were their occurrence, and so impactful were their results, that many Louisiana colonists regarded storms as a rite of passage, one they expected to experience as they made their way to and livelihoods in the new colony.

These storms also curtailed the ability of French colonial Louisiana to flourish in the early decades of the eighteenth century as the financial strain of these storms added to financial crises and disinvestment by the French Crown as more profitable colonies in the French Caribbean drew attention away from the struggling colony. As reported by Governor Bienville in 1719, “misery reigns always in Louisiana,” mainly due to the lack of human and material resources required to combat the many issues facing Louisianans, including hurricanes.

After Louisiana shifted to Spanish control in 1762 following the Seven Years’ War, hurricanes again impacted the colony’s development. Back-to-back storms between 1778 and 1779 flooded New Orleans and destroyed establishments at two colonial forts—La Balize at the mouth of the Mississippi River and Tigouyou along Lake Pontchartrain, as well as along Bayou St. John. The 1779 storm made landfall at New Orleans, smashing boats, fields, and provisions during the American Revolution, right after Spain had declared war on Great Britain. According to Governor Bernado de Gálvez, the “impetuous hurricane” came upon them in “less than three hours,” destroying ships that were in the process of attempting to seize the British fort at Baton Rouge, delaying the plans for invasion a full ten days. This hurricane would become known as “Dunbar’s Hurricane” because William Dunbar, a Scottish-American explorer and naturalist, was in New Orleans at the time and recorded observations on how hurricanes rotated around a central vortex and progressed forward. Dunbar later presented his observations to the American Philosophical Society in 1801, setting the basis for a new understanding of hurricane movements and scientific study. In 1780, just one year after the 1779 hurricane, another devastating storm destroyed crops, tore down buildings in Grand Isle and New Orleans, and sunk nearly every vessel afloat on the Mississippi River and surrounding lakes. Other hurricanes in 1781, 1793, 1794, and 1800 added to Louisianans’ misery when coupled with devastating fires in 1788 and 1794 and floods in 1788.

As Louisiana transitioned very briefly back to French rule before the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, Louisianans could do little except react in the aftermath of these storms. The storms had significantly impacted the colony’s development under the French and Spanish, shaped the success of different settlements, and even played a role in wartime decisions. Nevertheless, with each passing storm, Louisianans (and others) grew to expect their seasonal results, whatever they might be. In that sense storms became less an oddity one might occasionally experience in passage or settlement, and more a regular occurrence to permanent residents along Louisiana’s coast.

Nineteenth-Century-Louisiana Hurricanes

At the turn of the nineteenth century, Louisianans’ understanding of hurricanes changed. The publication of William Dunbar’s discovery on the movement of hurricanes and their rotational vortex, coupled with the transition of Louisiana from a French colony to an American territory and eventual state, raised interest in Louisiana hurricanes over the century. Two things drove this growing interest: first, the increasing economic value of the region that made each hurricane’s impact devastating; second, the American cultural fascination with disasters of all types in the nineteenth century, especially those caused by natural hazards like hurricanes.

Mechanical advancements in the nineteenth century, such as the inventions of the cotton gin and the steamboat, revolutionized Louisiana agriculture and transportation. Moreover, with the boom of the cotton, sugar, rice, and lumber industries, Louisiana’s economic prospects changed substantially. These changes made a hurricane’s impact potentially ruinous, as the economic stakes grew more prominent each storm season, which usually fell during peak harvesting periods. A total of forty-two major storms impacted the state between 1800 and 1900, and Louisiana experienced more than one storm in a year ten times. Of these forty-two storms, eight played a central role in shaping life and popular memory in the nineteenth century.

The 1812 storm, for instance, struck at the outset of the War of 1812, again impacting Louisiana during wartime. The storm caused $6 million in damages as it submerged New Orleans in fifteen feet of water and resulted in one hundred deaths. It also sparked panic as residents heard rumors that the British fleet stationed in the Gulf had captured Fort St. Philip on its way to New Orleans. The British, however, had also suffered: the troops ending up scattered across the Gulf after the fort went underwater due to the storm surge. Following the war’s conclusion, another rumor spread that an 1818 hurricane was also responsible for sinking ships of Louisiana’s notorious pirate and newly minted war hero, Jean Lafitte.

The next two notable nineteenth-century storms raised international awareness of Louisiana’s hurricane experiences. The first was the 1831 Great Barbados-Louisiana Hurricane, which devastated Barbados before making landfall at a small fishing village on Grand Isle. It caused significant damage to sugarcane crops from Pointe a la Hache to Baton Rouge. It also wiped out the orchards in Plaquemines Parish. A few days later, a second storm ruined cotton crops from Baton Rouge to Alexandria.

Following the twin storms of 1831, the 1837 Racer’s Storm severely damaged sugar and cotton crops along both sides of the Mississippi River. It also destroyed a lighthouse along Bayou St. John, the first built by the US government outside of the original thirteen British colonies. Coinciding with the nationwide financial Panic of 1837, damages from the Racer’s Storm were significantly more impactful. Multiple storms that followed in 1846 and 1852 changed the landscape of two Louisiana barrier islands, Cat and Chandeleur, as storms carved out new cut-throughs and boat channels.

While the storms up to the 1850s had been devastating, the storms that followed were memorable for their economic and cultural impacts. The 1856 Hurricane, also known as the Last Island Storm, had wide-reaching implications in shaping the national impressions of Louisiana hurricanes. As the strongest hurricane on record to make landfall in Louisiana at that time, the storm hit the famous resort town of Last Island, destroying nearly every structure, including the hotels and casinos; drowning at least 198 people on the island; and causing nearly 300 fatalities statewide. Reports of the storm’s impact were made even more horrific by news that four hundred vacationers were left stranded and forced to face the storm after the ship Star, sent to evacuate them, had blown off course. The storm also split the island in two, creating the new name “Last Islands” and leaving much of the original island unrecognizable. Following the hurricane, the disaster became the focus of national news as several survivors published first-hand accounts, and well-known Louisiana writer, Lafcadio Hearn, published the novel Chita: A Memory of Last Island.

The 1860s through the1880s saw a slew of storms cause damage at peak moments of political and economic strife. The state was hit three times in 1860 by storms that impacted major agricultural production regions in southeast Louisiana. The second storm of 1860 left $1 million in damages. Then, as the state entered the Civil War, Louisiana was offered a small respite from seasonal storms until 1865, when an extreme storm hit southwest Louisiana, destroying Niblet’s Bluff just after the close of the war. As Louisiana lay in ruins not only from the war but also from the hurricane, debates over rebuilding levees and providing for hurricane victims muddled with Reconstruction Era politics over federal intervention in state expenditures, causing strife in recovery. Finally, a storm in 1875 and two storms in 1879 caused similar damage to the areas impacted by the 1865 hurricane, again worsening economic conditions for the southwestern region.

The 1870s storms, however, were nothing compared to the devastating 1886 Indianola Hurricane that struck the Sabine Pass region. While destroying Indianola, Texas, the storm also left significant damage in Cameron Parish, particularly at Johnson Bayou, where nearly 110 people died as a twelve-foot storm surge swept inland. Similarly devastating was the drowning of seven thousand cattle in the parish and the loss of rice, sugarcane, corn, and cotton crops from Cameron to Plaquemines Parishes.

In 1888 Louisianans suffered from one of the most extensive hurricanes since the Racer’s Storm of 1837. The storm took out all telegraph and phone wires in New Orleans, including electrical cables installed around the time of the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition and World’s Fair in 1884, leaving the city in near darkness as it passed through the area. As a result, rice, sugarcane, and cotton crops across southeast Louisiana, all close to harvesting, were ruined. Coal ships in New Orleans’s harbor also sunk, equating to nearly $2.7 million in damages.

This devastating storm would pale compared to the 1893 Cheniere Caminada Hurricane that hit five years later. Storm damage stretched from Louisiana to Mobile, Alabama, and residents of Cheniere Caminada, at the time a small fishing village, were wiped off the map. More than two thousand people died across the region, making it one of Louisiana’s deadliest hurricanes. It also ended up being one of the costliest, causing $5 million in property losses.

Twentieth- and Twenty-First-Century Storms

From 1900 through the present Louisiana hurricanes have played a defining role in state and national disaster history. These storms have influenced a range of issues, from federal disaster relief policy to hurricane naming practices. Most importantly, these are the storms most often remembered in Louisiana’s hurricane history, especially as they mark current residents’ lives and serve as the most recent comparisons for each new hurricane season.

While the twentieth century started with a grievous hurricane, the 1900 Galveston Storm, it did not directly affect Louisiana except for outer-edge wind, rain, and storm surge. The following year an August 1901 storm struck Grand Isle, causing substantial flooding as the Mississippi River rose and a levee broke just outside New Orleans. Damage was extensive, totaling more than $1 million, but only ten lives were lost.

Louisiana experienced two additional storms—in 1906 and 1909—before suffering from a double hit in 1915. The first, an August storm, made landfall west of Galveston, Texas, but sent winds as far east as Mobile, Alabama, while producing powerful tides that flooded Cameron, Grand Cheniere, and Marsh Island. Between Louisiana and Texas damages totaled around $50 million. In September a second storm produced significant winds and floodwaters that directly impacted New Orleans and the surrounding area. In the town of Leeville, for example, ninety-nine out of one hundred buildings were destroyed. New Orleans quickly became submerged as levee overtopping along Lake Pontchartrain caused flooding in the western portion of the city. An additional levee failure near the Carrollton neighborhood overwhelmed the city, leading to four wet days as New Orleans’s drainage system struggled to pump water out of flooded areas. Over 275 people died due to the storm, many in the low-lying areas of the state, despite new efforts by the US Weather Bureau to provide advance warning of the storm’s possible impacts following lessons learned from the 1900 Galveston Storm. In the end the storm left the state with $13 million in damages, $5 million in New Orleans alone. Meanwhile, the ten-foot-high levee constructed outside the city drew considerable consternation following the storm as many felt it was no longer high enough to protect the city and its residents.

Between 1915 and 1947 Louisiana experienced nine additional storms, all of which caused damage to coastal areas. No region of the state was spared.

The United States’ entry into World War II resulted in changes to hurricane tracking systems as fears of enemy use of weather reports caused the military to censor weather tracking data. In 1944 the US introduced a hurricane code-naming system for use exclusively by military meteorologists in relaying information about impending storms in the Pacific Theater and, later, the home front. Using all-women’s names for storms, this code-naming system, which was inspired by George Stewart’s popular novel Storm, first relied on military meteorologists’ girlfriends’ or wives’ names. Following the war this code-naming system was discontinued as the meteorological storm trackers transitioned back to peacetime activities.

In both 1947 and 1948 storms struck on Labor Day weekend. This set of twin Labor Day storms caused confusion as forecasters tried to explain the events of the Labor Day storm of “this year” versus the Labor Day storm of “last year.” Both storms caused significant damage in the state. The 1947 Ripper, as it was called, demonstrated the dire need for tidal protection levees in New Orleans as much of the city flooded, leaving much of Old Metairie under four or five feet of water. The 1948 Labor Day Storm caused heavy damage to the burgeoning offshore oil industry. Fury over misunderstandings—as some people thought the 1948 warnings were mere rehash of the previous year’s storm—caused the US Weather Bureau to review its stance on naming hurricanes. The following year the bureau implemented a new naming system similar to the code-naming system used during World War II. Instead of an all-women naming list, they used the Military Phonetic Alphabet as its basis with each year’s list beginning with Able and ending with Zebra. After a few years though, the US Weather Bureau reverted to the women-only naming list used during the war. Beginning in 1954, storm names nationally would rotate through a list of pre-selected women’s names with a new list in use each year to prevent confusion.

Louisiana’s named storms stick out not only for their memorable names but also for their devastation. The 1950s and 60s set the stage for named Louisiana storms that became some of the state’s most recognizable—or well known—disasters. As the first named storm to impact the state significantly, Hurricane Flossy caused extensive coastal erosion in the Mississippi Delta in 1956. The notorious Hurricane Audrey followed in 1957, hitting southwest Louisiana hardest. Audrey caused $120 million in damages and left nearly 95 percent of the buildings in Cameron Parish destroyed while spawning tornadoes as far east as New Orleans and Arnaudville.

Louisiana also suffered consistent battering by storms in the 1960s, as Hurricanes Ethel, Carla, Hilda, Betsy, Camille, and Donna all wreaked havoc on the state. During Hurricane Carla, for instance, multiple oil rigs moved eight to ten feet toward the coast, despite anchoring before the 1961 storm. Meanwhile, back-to-back storms in 1964 and 1965 with Hurricanes Hilda and Betsy wrought damage to New Orleans and surrounding areas. Hurricane Betsy, in particular, was an extremely damaging storm, with winds that gusted to Alexandria and Monroe and brought the worst flooding to New Orleans in decades. Its final damage total—$1 billion—resulted in its nickname “Billion Dollar Betsy.”

Following Hurricane Betsy, the US Congress created the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) through the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968, meant to help reduce flood damages through the restriction of floodplain development and the purchase of federal flood insurance protection. Seen as a way to mitigate the impacts of flooding caused by major storms like Hurricane Betsy, it was the first step to controlling areas exposed to repeat flooding. The profound damage wrought by Betsy propelled the launch of the national program, which continues to shape flood policy in the United States, both in private and public markets.

In 1969 Louisiana experienced one of the most intense hurricanes known to make landfall in the country, Hurricane Camille. While Camille’s landfall was east of Louisiana, the state saw significant destruction from Venice to Slidell as significant wind, rain, and storm surge impacted the state.

Few extreme hurricanes struck Louisiana in the 1970s, but the state was not spared entirely as storms like Edith (1971), Carmen (1974), and Bob (1979) made landfall. Most notably, Hurricane Bob marked a new era of storm naming, in which hurricane names were no longer exclusively women’s names, but alternated between men’s and women’s names. As with the introduction of women-named storms in the 1950s, Louisiana also played a role in introducing the alternating man-woman system in the 1970s. Following pushback to the gendered naming system used for storms like Hurricanes Betsy and Camille, the National Organization for Women (NOW) met in New Orleans in 1969 and took on the mission to change hurricane names. Led by NOW member and feminist Roxcy Bolton of Florida, the group worked for ten years after the New Orleans meeting before the initiative succeeded.

In the 1980s Louisiana was spared significant hurricanes until a string of three, Danny, Elena, and Juan, struck in August, September, and October of 1985. While Hurricane Danny left a smaller amount of damage, Elena and Juan both caused substantial damage to coastal communities. In addition, the repeat storms also grossly impacted the struggling oil industry during an economic downturn, adding to the state’s woes.

The latter half of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s saw increasing storm activity as hurricanes like Florence (1988), Gilbert (1988), and Andrew (1992) wreaked havoc. Hurricane Andrew was the most significant of these three, having devastated Florida before reentering the Gulf and striking New Orleans. Over 1.25 million residents in central and southwest Louisiana evacuated from the storm, the largest evacuation in the state’s history.

Following Hurricane Andrew the state experienced regular storms like Opal (1995), Josephine (1996), Danny (1997), Frances (1998), and Georges (1998), but none of the size and scope of Andrew until the 2000s. Hurricane Lili marked the beginning of a new era of hurricane activity as it threatened to land in Vermilion Bay as a Category 4 storm in 2002. Ultimately, Hurricane Lili weakened to a Category 2 at the last minute, less devastating than originally predicted except for causing a slew of tornadoes in south central Louisiana. The next major storm, however, would top all that came before it, forever shaping Louisiana’s hurricane history.

In August 2005 Hurricane Katrina landed near Buras in Plaquemines Parish as a slow-moving Category 3 storm. Its resulting damages and loss of life made it the most destructive and costly disaster in US history, bringing international attention to Louisiana and prompting debate on effective disaster management at local, state, and federal levels.

While initially predicted to be a Category 5 storm, Katrina’s slow movements wreaked havoc on Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama as the storm progressed across the area over multiple days. Over 1.2 million people had evacuated ahead of time, but it was not enough. Approximately 100,000 people remained in the city as the hurricane struck, leaving 1,577 Louisiana residents dead in its aftermath.

Within a month of Hurricane Katrina’s impact, another storm hit Louisiana, this time on the state’s western side. Known as Hurricane Rita, it further exacerbated Louisiana’s already stretched-thin disaster response resources. Hurricane Rita decimated roughly 250 miles of coastal Louisiana when it landed in Cameron Parish, adding $18.5 billion to the growing total of damages left by Hurricane Katrina. A subsequent storm in 2008, Hurricane Ike, added to these woes for southwest Louisiana coastal communities, as it brought follow-up flooding that forced many to move further inland. As a result, by the time the next US census was taken in 2012, 33 percent of Cameron Parish’s population had moved from the area.

Hurricanes Gustav and Ike in 2008 threatened Louisiana—much like Hurricanes Katrina and Rita did in 2005—impacting the state back-to-back in similar regions. Unlike with Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, though, Louisiana did not suffer the same level of extensive damage from these 2008 storms. While Gustav ended up sparing the New Orleans area, it impacted the parishes of Terrebonne, St. Mary, and Lafourche, resulting in 48 deaths. Meanwhile, strong winds stretched between Baton Rouge and Lafayette before dying out, leaving behind $6 billion in damages.

Before Louisiana residents caught their breath, another storm named Ike loomed in the Gulf. Heading west to Galveston before curving to Houston, the storm threatened to sweep towards the Louisiana border, impacting coastal areas that had evacuated just a week before. Unlike Gustav, Ike held much of its intensity until landfall, keeping its width, which stretched six hundred miles wide, across the region as it traveled inland. The resulting strong tidal surges impacted coastal marshes and brought $38 billion worth of damage to the Texas-Louisiana border area.

The next storm to impact Louisiana came in 2012. Hurricane Isaac pushed such a significant storm surge into the Mississippi River that it flowed backward for twenty-four hours while flooding areas of Plaquemines Parish with twelve feet of water. The storm then reentered the Gulf below New Orleans, looking like it would re-form into a tropical storm before dissipating again.

Following Hurricane Isaac, Louisiana was spared a direct hit until August 2017, when Hurricane Harvey landed on the Louisiana-Texas border. As a devastating Category 4 storm, Hurricane Harvey ended twelve years of minor hurricanes since the devastating 2005 season. The slow-moving storm produced significant rainfall across Texas and Louisiana, with many areas receiving more than forty inches of rain. Storm-induced flooding caused thousands of homes to be inundated and resulted in the need for more than seventeen thousand rescues. Like during Hurricane Katrina, volunteer rescuers from Louisiana, including many with various “Cajun Navy” groups, assisted those stranded in flooded waters.

In 2020 Louisiana entered another era of intense hurricane activity, starting with Hurricanes Laura and Delta. Hurricane Laura made landfall in Cameron Parish as the strongest and most destructive Category 4 storm to hit Louisiana since the 1856 Last Island Hurricane. Traveling inland through the parish, it wreaked havoc in southwest Louisiana, particularly along the coastal Cameron Parish and in Lake Charles. With strong winds, coastal flooding, and storm surge, its losses equated to $19.1 billion and resulted in thirty deaths in Louisiana. With its impact on agriculturally rich southwest Louisiana, the storm did more damage to agriculture than Hurricanes Katrina and Rita combined. Similarly, the hurricane significantly impacted many oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico, shutting down 58 percent of oil and 45 percent of natural gas production as rigs were evacuated.

Six weeks after Hurricane Laura, a second major storm, Hurricane Delta, struck southwest Louisiana near Creole. While weaker than Hurricane Laura at impact, Delta’s blow worsened damage impacts to areas still in recovery. This also made recovery efforts all the more difficult in the state, as tens of thousands of Louisianans were hard-hit in the same hurricane season. Due to an election cycle and delayed recovery funding, regions of this area continue to face slow recovery as of this writing in 2023.

In 2021 another deadly storm impacted Louisiana, quickly becoming the second-most damaging and intense hurricane to land in Louisiana, ranking behind Hurricane Katrina. With winds of 150 mph at landfall, Ida tied Hurricane Laura and the 1856 Last Island Hurricane as the strongest to impact the state. With devastating flooding and tornados, particularly to New Orleans and surrounding areas, occurring on the anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, Ida was scarily familiar to the state. Unlike during Hurricane Katrina, though, New Orleans’s levees held up to the storm’s impact, but downed power lines left more than a million people without electricity in the state’s eastern half. The outage lasted weeks for many, and in some areas like Terrebonne Parish, it lasted months. As the fourth-costliest hurricane to impact the United States, Ida caused $75.25 billion in damages and thirty deaths in the state. Tragically, due to the extended power loss, many Louisianans turned to using generators, resulting in 141 hospitalizations and four deaths due to carbon monoxide poisoning.

Conclusion

Louisiana’s hurricane history makes one thing clear: hurricanes will always return. The state’s position along the Gulf of Mexico makes it consistently vulnerable to intense storms, and with each passing year, Louisiana residents know the likelihood of impact is high.

Louisiana’s hurricanes have shaped its history. Hurricanes have impacted choices about where to settle and when to leave an area. They have impacted the politics and economics of how rescue and recovery decisions should be made. They have influenced cultural products, like literature, music, art, television, and films. And they have even impacted how Louisianans (and others) name storms. But, more than anything, they have impacted Louisianans’ lives, marking them each year with a new season of possibility and potential devastation, and they will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.