French Colonial Louisiana

The period of French colonial control of Louisiana dates from 1682 to 1800.

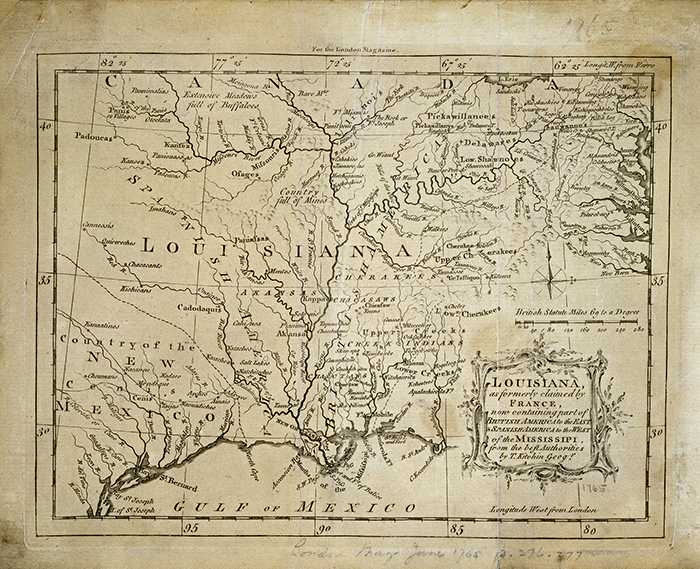

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

This map, dated 1765, shows the Louisiana Territory as claimed by France.

French colonial Louisiana refers to the first century of permanent European settlement in the Lower Mississippi Valley. Native Americans, Europeans, and Africans contributed to the development of a complex frontier society at the geographic nexus of the Americas. Although the French regime considered Louisiana to be a failed colonial enterprise, the diverse peoples of the territory proved essential to the nature of imperial relations among French, Spanish, English, and American interests during the eighteenth century. The multicultural composition of the Lower Mississippi Valley remained strong even after the cession of Louisiana to Spain in 1763, the retrocession to France in 1800, and the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, effectively making the state of Louisiana both representative of the diversity of the United States and unique for its distinctive colonial past.

The La Salle Expeditions, 1682–1689

Spanish explorers “discovered” segments of the coast of the Gulf of Mexico during the sixteenth century. The chief goal of Juan Ponce de León, Hernando de Soto, and other Spaniards was to find a navigable waterway to the Pacific Ocean. Like the Spanish, French colonial officials in Canada harbored dreams of crossing North America by water. Rumors of the existence of a “great river” connecting the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico reached French missionaries and traders during the 1660s. The governor of Canada commissioned Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit missionary, and Louis Joliet, a French merchant, to lead a small expedition down the great river. They reached the Arkansas River in 1673, but went no farther after the Quapaw warned them of supposedly hostile native groups and Spanish posts in the Lower Mississippi Valley.

In 1677, Rene-Robert Cavelier, sieur de la Salle, and Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac et de Palluau, received a fur trade monopoly in the Illinois Country. The trading scheme produced little profit. La Salle then shifted his attention to the development of colonies farther south along the great river. Joined by his lieutenant Henri de Tonti and several adventurers, La Salle entered the waters of the great river in February of 1682. They built temporary stockades at Fort Prudhomme (near present-day Memphis) and the Arkansas River. On April 9, 1682, at the junction of the bird-foot delta near the Gulf of Mexico, La Salle claimed the river and its drainage basin for King Louis XIV, thus the name Louisiana. He gave the name Colbert to the great river in recognition of his patron and French finance minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert. He then calculated what he thought was the mouth’s latitude, returned northward to Canada, and started planning for the establishment of a colony on the Colbert River.

La Salle secured a contract for the colonization of Lower Louisiana from Louis XIV in 1682. Two years later, La Salle’s small fleet left the French port of La Rochelle, with roughly 100 soldiers, a year’s worth of supplies, and 280 men, women, and children. They stopped at the French island Saint Domingue before making landfall somewhere between Grand Isle and the Atchafalaya Bay in December 1684. Because of a latitudinal miscalculation, the La Salle expedition continued west until it reached the entrance of Matagorda Bay in present-day Texas. La Salle sent one ship back to France with news of the colony’s uncertain future. He then led three overland expeditions in search of the missing Colbert River. Most of his companions either died or deserted during the first two trips. On the third expedition of 1687, several men murdered La Salle and continued moving east until they reached the Arkansas River and then traveled onward to Canada and France. A Spanish search party found the abandoned Matagorda colony in 1689 and surmised that natives had killed or captured all of the French colonists.

La Salle’s expeditions brought Europeans in contact with Native American peoples whose ancestors had resided throughout the Mississippi River Valley for more than a thousand years. Historians have identified features of the Mississippian Culture (1200–1700) that connected Native American groups from Illinois to Louisiana and from Oklahoma to Georgia. Located in present-day northeastern Louisiana, the archaic archaeological site known as Poverty Point represents one of many centers of commercial and ceremonial activity along the “highway” of the Mississippi River that included elaborate earthworks and mounds dating back to approximately 2000 BC.

Members of La Salle’s expeditions encountered similar human-made earth structures among the Natchez peoples. Known by archaeologists as the Fatherland site, the Grand Village of the Natchez included mounds with a temple and the chief’s residence atop them. It was also common for Native American peoples of the Mississippi River Valley to introduce European strangers to the calumet ceremony, a pipe-smoking ritual that created both temporary and long-term cooperation in matters of diplomacy, trade, and warfare. Approximately 70,000 Native Americans inhabited Lower Louisiana by the end of the seventeenth century, a population greatly diminished on account of the contagion of European diseases that began more than a century earlier with Spanish-Indian contact.

The First French Settlements, 1699–1713

Following the War of the League of Augsburg (1688–1697), Louis XIV of France moved aggressively to expand French territories, and the French minister of the marine Louis de Phélypeaux, Comte de Pontchartrain, secretly made plans to establish French posts in Louisiana. In doing so, Pontchartrain intended to undermine the colonial interests of the English, Dutch, and Spanish along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville et d’Ardillières led the first French expedition to the vicinity of present-day Biloxi in 1699, followed by a year of exploring the Mississippi and Red River Valleys and making contact with the Natchez and other petites nations. In 1702 Iberville moved the colony’s base of operations to Mobile, where roughly 140 French speakers hoped to develop closer trade and military ties with the Choctaw and Chickasaw in order to check British expansion. Before permanently leaving Louisiana, Iberville vested considerable authority in his brother Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, sieur de Bienville, and his cousin Pierre Charles Le Sueur.

French Crown officials paid little attention to the needs of Lower Louisiana during the early 1700s because of their involvement in the War of Spanish Succession (1701–1714). Lacking official support, Iberville and his elite associates were unable to implement the conventional French mercantilist practice of exploiting natural resources (furs, minerals, cash crops) from colonial territories. To compensate for supply shortages, French colonists relied heavily on the slave labor and agricultural acumen of neighboring Native American groups. To protect against the slave raids and military advances of British-allied tribes such as the Creek, Native American villages in the vicinity of Mobile developed close working relationships with the French. The Choctaw and Chickasaw were especially influential in how the French developed strategies to defend against British encroachment throughout frontier areas east of the Mississippi River. The close interconnectedness of Native Americans and Europeans during this early colonization phase convinced historian Daniel Usner to describe French colonial Louisiana as a “frontier exchange economy” influenced by local and regional networks as well as transatlantic and global movements.

A 1708 census recorded 339 individuals in the French colony: 60 Canadian coureurs des bois (woods runners or backwoodsmen); 122 soldiers, seamen, and craftsmen employed by the Crown; and 157 enslaved Indian and European men, women, and children. A handful of Catholic missionary priests traveled through or settled in the colony, though with limited success at evangelizing Native Americans and gaining support from the French laity. With no clear leader, the political organization of Louisiana bore modest resemblance to Canada, its neighbor to the north. Bienville, then a teenager, functioned as the commander of Mobile until Pontchartrain sent the ordonnateur (commissary) Bernard Diron d’Artaguette to investigate and expel the Le Moyne family from Louisiana. Quite the opposite happened, as Bienville became acting governor in 1711, later replaced in 1713 by the founder of Detroit, sieur Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, as the first official governor of Louisiana.

Companies and Slavery, 1713–1729

Antoine Crozat, councilor and financial secretary to Louis XIV (1638–1715), received a fifteen-year commercial monopoly over Louisiana in 1712. Crozat attempted to organize the colonial government of Louisiana according to Canadian standards by dividing military and civil affairs among the three offices of commandant, governor, and ordonnateur. He also created a court known as the Superior Council. Technically, Crozat’s company fell under the authority of the governor of Canada, while church matters remained under the jurisdiction of the bishop of Quebec. In reality, daily life in Lower Louisiana remained largely independent of Canadian oversight.

The European population increased from approximately 200 to 500 inhabitants during the Crozat years (1713–1717). Fur trading remained the primary source of income for the colony. There were also rather unsuccessful attempts, first, to trade with Spanish and French West Indian posts, and, second, to harvest silk, indigo, and other cash crops. Louis Juchereau de St. Denis conducted an expedition up the Red River, resulting in the establishment of a French post at Natchitoches. Cadillac made a similar trip in search of lead mines, which resulted in the foundation of Fort Rosalie near present-day Natchez. The French also benefited from the start of the Yamasee War in 1715, a conflict between colonial South Carolina and Native Americans, which took the attention of the English away from making military and economic alliances with the Creek and Chickasaw.

Crozat pulled out of the company contract in 1717. The Scotsman John Law then assumed control over all commercial affairs in Louisiana under the auspices of the Company of the West, later called the Company of the Indies. Law obtained the company charter as part of a larger scheme to transition France to a paper currency system, reduce the Crown’s debt and restore its credit, and bring wealth to Law and his business associates. Law’s financial plan ultimately failed in 1720, when the so-called “Mississippi Bubble” burst.

Despite the company’s failures, Law’s investment in Louisiana amounted to considerable changes in the organization and composition of the colony, which lasted through the 1720s. Bienville moved the colonial capital from Mobile to New Orleans in 1718. Historian Shannon Lee Dawdy described early New Orleans as a “rogue,” “wild,” even “savage” colonial city in the sense that its leading elite inhabitants tried and largely failed to translate their Enlightenment ideals of social order to the swampy banks of the Mississippi River. Memoirs and letters of early residents abound on the topic of New Orleans’s lack of urbanity and wealth of problems.

Outside New Orleans, the company granted land concessions to wealthy Frenchmen along the Mississippi River. Upstart settlers and established elites smuggled trade goods throughout the Mississippi Valley and Caribbean in order to avoid the mercantilist policies of the French Crown. The growing labor force was made up of peasants and indentured servants (petits gens) from France and Alsace, impressed criminals (forçats), Swiss mercenaries and poorly trained French soldiers, and women from Parisian hospitals and asylums, ultimately raising the European population of Louisiana to around 5,000 by 1721. However, the number of European settlers dropped to fewer than 2,000 by the end of the 1720s, due largely to high death rates and the decision of many to abandon the colony.

Roman Catholic priests and nuns contributed to the social development of French colonial Louisiana throughout the early eighteenth century. Paul du Ru, a Jesuit priest, attempted to establish missions among the petites nations, or small tribes, of the Lower Mississippi Valley during Iberville’s brief tenure in Louisiana. Several priests of the Foreign Mission worked as missionaries among Native Americans and chaplains among French settlers. The bishop of Quebec granted ecclesiastical jurisdiction over the European population (and those enslaved by Europeans) of Lower Louisiana to the Capuchins. The Jesuits, in turn, were responsible for the missionization of Native Americans outside the confines of French posts. This bipartite organization of the clergy led to considerable conflict, often resulting in the deterioration of Indian missions and lay-clerical relations.

Nicolas-Ignace de Beaubois (1689–1770), Jesuit superior of Lower Louisiana, established a permanent male missionary presence in and around New Orleans in 1727. A troupe of twelve Ursuline nuns also arrived at New Orleans in 1727. Marie Madeline Hachard, the youngest of the women in habits, left a record of her life as a missionary, which was published in France for the edification of young women. In addition to their roles as religious leaders, Catholic priests and nuns busied themselves with mundane aspects of life in French colonial Louisiana. They bought and sold enslaved people. They negotiated with company and Crown officials for salaries, property, and power. In short, their experiences were not entirely different from those of other European settlers.

The forced migration of approximately 6,000 enslaved Africans constituted the most significant demographic alteration to French colonial Louisiana during the 1720s. Approximately two-thirds of the enslaved came from the Senegambian region of West Africa, while the rest came from the Bight of Benin and Angola. They brought with them knowledge of rice, corn, tobacco, cotton, and indigo cultivation, as well as an assortment of technologies and skills related to craftsmanship, all of which were considered useful for the development of a fledgling colony in the Americas. Enslaved Africans and Indians interacted on a daily and intimate basis, effectively undermining the intention of French slaveholders to control the thoughts and actions of their human property. In 1724 French officials implemented the Code Noir in hopes of regulating the everyday lives of enslaved and free people of African descent in Louisiana, much as governments had done in other French colonies throughout the Caribbean. Such regulatory efforts produced mixed results, with many enslaved Africans taking advantage of the frontier conditions of Louisiana by creating runaway communities (le marronage) in cypress swamps (la ciprière) throughout the Lower Mississippi Valley and possibly planning slave revolts against their white owners.

By 1732 enslaved Africans accounted for approximately 65 percent of the total population of Louisiana. The large majority of enslaved Africans lived and worked on private plantations along the Mississippi River away from New Orleans. Near the capital, however, many enslaved Africans worked on plantations owned by the governor, the Catholic Church, the Company of the Indies, and later the king. These enslaved men, women, and children made up 12 percent of New Orleans’s population in 1726. Until the Spanish colonial period only one slave ship arrived at Louisiana after 1736, thus setting the stage for the development of what historian Gwendolyn Midlo Hall called an “Afro-Creole” culture in eighteenth-century Louisiana. People of African descent born in the colony, or Afro-Creoles, would constitute more than 50 percent of the total population of Louisiana by the end of the French colonial period in 1769.

Military and Economic Difficulties, 1729–1754

Economic development in French colonial Louisiana remained limited during the 1720s. The company established Fort Chartres as a way to advance the fur trade in the Illinois Country, only to be greatly disrupted during the wars between the French and the Fox Indians of the late 1720s. English encroachment upon the fur trade in present-day Mississippi and Alabama also diminished French influence among neighboring petites nations. And despite the marginally successful cultivation of tobacco near Fort Rosalie, the so-called Natchez Revolt of 1729 contributed to an economic downturn in Lower Louisiana that lasted through the 1730s.

On the morning of November 28, 1729, Natchez warriors killed more than 200 French men, women, and children, and captured around 300 enslaved Africans and 50 French women and children. Rumors of a Natchez conspiracy against Fort Rosalie preceded the attack, in which some enslaved Africans played a role. Approximately 10 percent of Louisiana’s white population died in the attack. The French government responded to the Natchez revolt by disbanding the company and reclaiming Crown authority over Louisiana. Under the leadership of Bienville and with the assistance of the Illinois, Tunica, and other Native American groups, French soldiers spent the next decade conducting a series of military campaigns against the Natchez and Chickasaw. The French had two chief objectives: first, to exterminate what remained of the Natchez, and second, to punish the Chickasaw for harboring Natchez refugees and trading with the English.

Military expeditions against the Natchez and Chickasaw produced mixed results. French forces failed to achieve any clear victories over the Chickasaw, while their ties with the Choctaw became ever more tenuous. At the same time, French officials attempted to revitalize the economy of Louisiana by encouraging the production of tobacco and trade with French ports such as La Rochelle and Bordeaux, again with only moderate success. Inflation of the currency and poor weather, including a devastating hurricane, did not make their jobs any easier. Much of the blame for the colony’s decline fell upon Bienville, who was finally replaced as governor in 1742 by the Marquis Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil de Cavagnial. By 1746, the population of French colonial Louisiana had shrunk to approximately 3,200 whites and 4,730 African-descended people, due primarily to the return of many settlers to France, the low number of new European immigrants, the near cessation of the importation of enslaved Africans, and low levels of reproduction among both European and African populations.

With the governorship of Vaudreuil came a previously unattained level of prosperity in Lower Louisiana. From 1744 to 1755, colonial leaders realized increases both in trade and population, this despite French involvement in the War of Jenkins’ Ear (1739–1742) and the War of Austrian Succession (1740–1748). Some large plantation owners along the Mississippi River replaced tobacco with the more profitable indigo, though small-scale farming of other cash crops and lumbering continued. Louisiana merchants enhanced trade with Spanish ports in Cuba, Mexico, and Florida. Trade between Dauphin Island (near Mobile) and Pensacola, in particular, remained strong through much of the 1750s. Some historians estimate a 50 percent increase in population during this period, due primarily to the arrival of fils de cassette (coffer girls), Alsatians, and French soldiers. Most Europeans lived in the vicinities of New Orleans, Mobile, or Natchez. The increase in plantation productivity also marked an increase in the importation of enslaved Africans, most of whom came from the French West Indies.

Disputes among the Choctaw, Chickasaw, French, and English increased during the 1740s and 1750s. Red Shoe, a Choctaw chief, encouraged portions of the Choctaw nation and the Alabamas to trade with the English. Vaudreuil, in an attempt to undermine Red Shoe’s intentions, organized a diplomatic ceremony for around 1,200 Choctaw to meet with French officials in 1746. Tension reached a high point when Red Shoe killed three French traders and Vaudreuil called for revenge. A Choctaw warrior ultimately assassinated Red Shoe. By 1747, the Choctaws were at war with each other, as villages drew battle lines according to English or French alliances. It was not until the French provided their Choctaw allies with sufficient supplies that a modicum of peace was restored in 1750. However, major military conflict between the French and Chickasaw resumed in 1752 when Vaudreuil ordered assaults on Chickasaw villages in present-day northern Alabama and Mississippi. The Chickasaw effectively repelled the French expedition with the help of the English.

The End of French Rule, 1754–1769

Louis Billouart, Chevalier de Kerlerec, arrived at New Orleans in 1753. Three interrelated matters dominated the administration of the new governor: internal politics, French-Indian relations, and the Seven Years’ War (1754–1763, also called the French and Indian War). Kerlerec’s Indian policy got off to a rocky start when he hosted a meeting with the Choctaw at Mobile but failed to offer his guests sufficient gifts and trade goods. The deplorable state of Louisiana’s forts and soldiery convinced Kerlerec that he would need the assistance of the Native American population if he wanted to protect the imperial interests of the French against the English. Reinforcements of questionable quality arrived at intervals during the 1750s and early 1760s, along with the new ordonnateur Vincent Gaspar Pierre de Rochemore. Rochemore and Kerlerec, though rivals, convinced segments of the Choctaw, Alabamas, Upper Creek, and Cherokee to disrupt the Chickasaw-English alliance throughout the frontiers of the American interior. Insufficient supplies made it difficult for Kerlerec to compete with English traders and soldiers coming out of South Carolina.

The 1760s saw the ousting of Rochemore as ordonnateur and the appointment of Denis-Nicolas Foucault as his replacement. Moreover, Jean Jacques Blaise d’Abbadie replaced Kerlerec as governor. D’Abbadie’s instructions from the Crown were clear: Begin liquidating French holdings in Lower Louisiana in accordance with treaties following the Seven Years’ War. After several years of diplomatic negotiations, the French convinced the Spanish to ally themselves against British interests in Europe and the Americas. The secret signing of the 1762 Treaty of Fontainebleau involved France’s Louis XV promising Spain’s Charles III the territory of Louisiana (including Illinois) and the so-called Isle of Orleans. However, the 1763 Treaty of Paris, which actually ended the Seven Years’ War, granted territories west of the Mississippi River (including New Orleans) to the Spanish and eastern territories (including Baton Rouge) to the English. Coinciding with the cession of French Louisiana was the suppression of the Jesuit order in 1763, which resulted in the expulsion of all but one Jesuit (Michel Baudouin) from the Lower Mississippi Valley.

It is not entirely clear why Louis XV so willingly ceded Louisiana to Spain. Most historians cite Louis XV’s interest in strengthening Franco-Spanish ties and relinquishing control over an economically burdensome colony. Regardless, the decision to cede Louisiana to Spain had little immediate impact on the local population. Approximately 1,500 people of European descent and 2,000 people of African descent resided in and around New Orleans in 1766. Pointe Coupée and Natchitoches also remained important French settlements after the cession of Louisiana to Spain. French trading continued throughout frontier regions west of the Mississippi River. A complex network of plantations lined the Mississippi River from the Balize (near the mouth of the Mississippi River in present-day Plaquemines Parish) through the German Coast (just above New Orleans in present-day St. Charles Parish) to Natchez. Levees, both natural and manmade, protected plantations from frequent inundation and functioned as a sort of road for overland travel. In 1766, St. Gabriel (just above Bayou La Fourche) became the site of one of the first Acadian settlements in Louisiana. Acadians continued to migrate farther west via the Atchafalaya River to the Opelousas and Attakapas districts of southwestern Louisiana during the late 1760s. Several frontier posts dotted the banks of the Mississippi River above the Arkansas River in the Illinois Country, including Cape Girardeau, Kaskaskia, Ste. Geneviève, and St. Louis.

French Creole inhabitants, and especially a small group of elite power holders, proved highly influential during the tenure of the first Spanish governor Antonio de Ulloa from 1764 to 1768. Major Charles Philippe Aubry, the French director-general of Louisiana, and Nicolas Foucault, the ordonnateur, remained the effective administrators of the colony until Ulloa enacted a dual Spanish-French administration in early 1767. Prior to then, Ulloa did not proclaim Spanish dominion over Louisiana and allowed the French flag to remain flying over the city of approximately 3,500 inhabitants. The passage of strict trade regulations by the Spanish in 1768 led Foucault and the powerful French Creole oligarchy to consider an insurrection. Ulloa left soon thereafter, only to be replaced by General Alejandro O’Reilly with orders to suppress what came to be known as the Insurrection of 1768. Joined by more than 2,000 troops, O’Reilly conducted a bloodless reoccupation of New Orleans later that year and proceeded to implement Spanish colonial institutions in Louisiana with the aid of Luís de Unzaga y Amezaga, the future governor of the colony.

French Influence in Spanish Colonial Louisiana, 1769–1800

The influence of Creole inhabitants (people of French and African descent born in Louisiana) remained strong during the first decade of Spanish control. Outside New Orleans, the colonial administration of Spanish Louisiana largely fell to the commandants of eleven posts (or districts) stretching along the Mississippi River from present-day Ascension Parish in the south to present-day St. Louis in the north. The francophone Creole population both resisted and adapted to the colonial reforms of Unzaga, although adaptation was initially difficult because of the onset of an economic depression during the early 1770s. British influence among Native American groups in Lower Louisiana persisted during the Spanish colonial period. Spanish officials attempted to curtail British advances and conduct Indian affairs according to French modes of gift-giving ceremonies, trade partnerships, and military alliances. Moreover, during a particularly disruptive ecclesiastical battle between French and Spanish Capuchins, Unzaga demonstrated an interest in reinforcing the religious customs of the French clergy. In 1777, Unzaga left office as governor of Louisiana in the wake of British operations in the Gulf of Mexico that were linked to the American Revolution.

Bernardo de Gálvez, the gubernatorial successor to Unzaga, oversaw the gradual but thorough reconciliation of the francophone population of Lower Louisiana to Spanish rule throughout the late 1770s and early 1780s. He introduced more than 1,500 Canary Islanders, or Isleños, and 500 Malagueños to Spanish Louisiana by 1779, many of whom would participate in military expeditions against British forces in West Florida. He also granted Creole Louisianans permission to conduct trade with ports in the West Indies and France. Francophone militiamen played a crucial role in Spanish campaigns against British forts at Baton Rouge, Mobile, Pensacola, and Natchez. These and other posts would ultimately come under Spanish occupation, resulting in an Anglo-Spanish treaty of 1783 that left much of the Mississippi Valley and territory south of the Ohio River to the Spanish.

Esteban Rodríguez Miró y Sabater, formerly Gálvez’s second-in-command during the West Florida campaigns, became acting governor of Louisiana in 1782. He oversaw several immigration schemes that served to dilute the French Creole population of Spanish Louisiana. Approximately 1,600 Acadians arrived at New Orleans in 1785, many of whom joined their kin in the Opelousas and Attakapas districts. Anglophone non-Catholics of the Natchez district represented a second major migration group to inhabit Spanish Louisiana during the 1780s. Ultimately Miró permitted approximately 3,500 former British subjects to make their residences in the tobacco-rich area of Natchez as long as they swore allegiance to the Spanish Crown and promised to baptize their children in the Catholic Church. By 1784, the total population of Spanish Louisiana was 32,000, up from 18,000 in 1777. The number had increased to more than 42,000 by 1788. Miró continued to entice new immigrants to Louisiana after a fire destroyed much of New Orleans in 1788, thus raising the population to around 48,000 by 1795. Though significantly greater than the rate of growth during the French colonial period, these numbers paled in comparison to a place like Kentucky, where the population increased from 30,000 in 1785 to more than 70,000 in 1790.

Francisco Luis Héctor, barón de Carondelet, became governor of Spanish Louisiana and West Florida in 1791. He continued Miró’s policy of asserting Spanish control of the Mississippi River from the Gulf of Mexico to the Ohio River. In addition to the threat of American territorial expansion, Carondelet faced increasing discontent among the francophone inhabitants of Louisiana following the French Revolution of 1789, the Haitian Revolution of 1791, and Spain’s declaration of war against France in 1793. Rumors of slave insurrections and a French invasion were common during the 1790s. Tension reached a high point in 1795 when Carondelet violently suppressed a slave conspiracy in Pointe Coupée. Edmond-Charles Genêt, French ambassador to the United States, also added to the worries of Carondelet with his plan, though never executed, to raise an army of Americans and French forces against Spanish Louisiana.

With the signing of the Treaty of San Lorenzo (also known as Pinckney’s Treaty) in 1795, Spain recognized the United States’s claim to territories east of the Mississippi River and shipping rights along the river. Delays in the implementation of the treaty lasted until 1798. In the meantime, Spanish and French officials negotiated a retrocession of Louisiana to France, culminating in an agreement of terms with the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso on October 1, 1800. Spain delayed the retrocession of Spanish territories west of the Mississippi River (including New Orleans but not including West Florida), to the dismay of Napoleon Bonaparte who was also handling a difficult military campaign in Haiti. By 1803, Napoleon had decided against expanding France’s empire in the Americas. Under pressure from Robert R. Livingston, the US minister to France, and James Monroe, a special agent sent to France by Secretary of State James Madison, Napoleon agreed to the Louisiana Purchase for 60 million francs on May 2, 1803. President Thomas Jefferson promptly ordered the Mississippi territorial governor William C. C. Claiborne to handle the transfer of the Louisiana Territory from Spanish to American control on December 20, 1803.