Les Petites Nations

Approximately forty ethnically and politically distinct North American Indigenous polities located in the Gulf Coast region and lower Mississippi River valley made up les petites nations.

PEABODY MUSEUM OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY

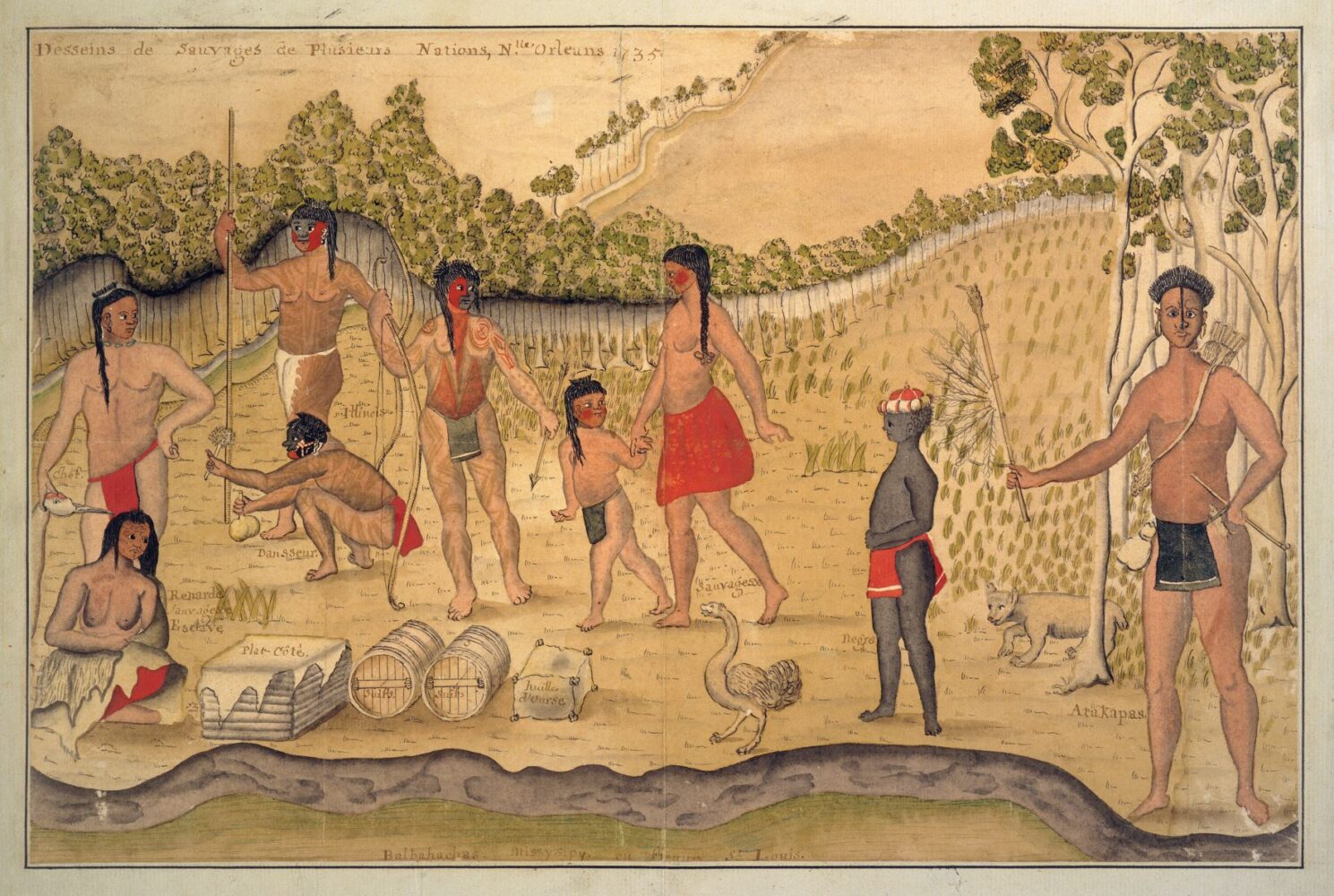

Desseins de Sauvages de Plusieurs Nations, 1735.

Les petites nations, or small nations, as they were generally known by the French in Louisiana from 1699 to 1763, were approximately forty ethnically and politically distinct North American Indigenous polities settled in the many coastal and woodland environs of the Gulf Coast and lower Mississippi River valley. They included the Taensas, Biloxis, Avoyelles, Houmas, Ishaks, Yazoos, Tiouxs, Tunicas, Acolapissas, Koroas, Chatots, Tawasas, Pensacolas, Mobilians, Pascagoulas, Apalachees, Mougoulashas, Chitimachas, Ofos (or Ofogoulas), Bayagoulas, the Grand and Petit Tohomés, and many others. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, these small nations belonged to six different language groups and could vary in size from fifty to two thousand people—in all totaling nearly twenty thousand persons ranging from the Escambia River in present-day northwest Florida, the Yazoo River in present-day central Mississippi to eastern portions of the Red River in present-day Louisiana. Although this population estimate would be halved by midcentury as the petites nations were reduced by decades of epidemics and warfare, it was a number not surpassed by the white settler and the free and enslaved African populations in the colony until the late 1770s. Despite being overshadowed by the more populated Indigenous polities of the interior such as the Creeks, Choctaws, and Chickasaws, the petites nations were integral to regional developments on the Gulf Coast and lower Mississippi River valley throughout the eighteenth century. Many of their descendants live in the states of Louisiana and Texas today.

The term “petites nations”—which generalizes many diverse and independent societies—was in reference to their small population sizes relative to the larger Indigenous polities of the interior. In one of many contrasts to the larger polities, the petites nations chose to invite European colonizers to establish settlements near their towns. These European settlements include Mobile, New Orleans, Biloxi, and Pointe Coupée, among others. These invitations were in keeping with a cultural practice of welcoming foreign refugees and speaks to how the petites nations viewed the French, with whom they partnered commercially and militarily as traders, hunters, farmers, interpreters, basket weavers, herders, boatmen, mercenaries, and fishermen. The labor and material exchange economy that developed from interactions between the petites nations, French colonial settlers, enslaved and free Africans, and other Indigenous populations in the region created a socioeconomic order where intercultural cooperation and negotiation became an indispensable feature for mutual survival in what historian Daniel Usner has described as the “frontier exchange economy.”

Origins and Alliance Building

Many polities that comprised the petites nations shared origins as refugees following the chaos from the successions of collapse of the mound-building Mississippian chiefdoms, which had dominated the continental interior from about 1050 CE to 1700 CE. Other polities, however, were not born of this collapse and seem to have inhabited the same general area for many years prior to the arrival of Europeans. Refugee communities would eventually form what anthropologists Charles Hudson and Robbie Ethridge termed “coalescent societies,” which join people from different religious, political, ethnic, and social backgrounds into a single polity. The Creeks, Choctaws, and Chickasaws coalesced in this manner at different stages during the late-seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Though the petites nations would sometimes incorporate or adopt outsider groups into their communities, they did not coalesce in the traditional sense defined here. They instead remained small and independent, yet highly resourceful and adaptive to a variety of human and environmental threats. Forming what historian Elizabeth Ellis has recognized as “multinational settlements,” the petites nations often established their communities near one another for protection and for the expansion of kinship and trade networks during times of crisis.

The calumet ceremony facilitated the continuance of these multinational settlements. Understood as a ritual involving the smoking of tobacco in a sacred feathered pipe, the calumet—French for “hollow reed”—had the potential to establish covenants between people from different polities, and it was an act that required regular renewal. While among the Illinois people in 1673, Father Jacques Marquette recorded that the Illinois “presented to us, according to custom, their calumet, which one must accept, or he would be looked upon as an enemy.” Marquette mused that “the calumet [was] the most mysterious thing in the world. The scepters of our kings are not so much respected; for the Indians have such a deference for it, that one may call it ‘The God of Peace and War, and the arbiter of life and death.’” Failure to take such customs seriously could have violent repercussions.

Proximity could produce a permanent unification between multiple polities, or it could be a temporary arrangement where small groups would migrate and settle in the territory of another before moving elsewhere as new opportunities permitted or, as in some cases, violence drove them apart. Colonial incursions increased conflict among neighboring petites nations, accelerating these migration cycles. In 1700 the Bayagoulas killed the men and adopted the women and children of the neighboring Mougoulashas. Migrating downriver from Chickasaw raids against their homes on Lake St. Joseph in present-day northern Louisiana in 1706, the Taensas settled near the Bayagoulas and were welcomed as replacements for the Mougoulashas. Within a few months, however, the Taensas attacked and killed the Bayagoula men and adopted the surviving women and children. They then invited the neighboring Chitimachas to celebrate this victory only to violently turn on their guests, killing and capturing many. This series of violent acts was likely a cultural response to population losses suffered from an exposure to war and epidemics. Migration and bloodshed of this sort escalated as eastern North America became an increasingly unstable place from the late-seventeenth to the early eighteenth centuries.

The Commercial Indian Slave Trade

English, Dutch, and French colonization of the Atlantic seaboard during the seventeenth century helped initiate numerous conflicts between Indigenous polities across much of the eastern third of the continent. For many Native nations, war captives, who were not adopted or sacrificed, would often be sold to Europeans for firearms and other tools in the commercial Indian slave trade. The introduction of firearms empowered and emboldened societies such as the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), who lived in present day southern Ontario, Quebec, and upstate New York, to expand the traffic in human captives far beyond rival neighbors. The confinement and movement of captives from these raids brought the added misery and death from Old World pathogens such as smallpox, measles, and influenza. These diseases accelerated the decline of many populations. By the late seventeenth century, whole Indigenous communities from the Great Lakes regions and Ohio River valley were displaced by raids from Haudenosaunee war parties. Small bands of refugees followed rivers south into the lower Mississippi River valley where they created new polities in both partnership and tension with other Indigenous groups already in place there. Early French explorations of the Mississippi River in the 1670s and 1680s observed signs of this distress as far west as the Arkansas River junction. Refugees, war, and large stretches of vacant lands betrayed a region in flux.

One such migrant group was the Mosopeleas, later known as the Ofos/Ofogoulas. Fleeing Haudenosaunee slave raids in the Ohio River valley, the Mosopeleas retreated down the Mississippi River, where members of their party were attacked and captured by the Quapaws. After reaching an accord with the Taensas, who were allied with the Quapaws, the Mosopeleas settled their communities alongside other petites nations towns at a busy and populated multinational settlement site on the Yazoo River that included Taensas, Tunicas, Yazoos, Tiouxs, and Koroas. René-Robert Cavelier, sieur de La Salle, observed this site in the 1690s during one of his explorations of the southern reaches of the Mississippi River. For the Mosopeleas, migrating and triangulating diplomacy this way was one means for combating violent threats.

As the English colonies spread south, so too did the commercial Indian slave trade. Charlestown’s inexhaustible needs for cheap labor brought alliances between the new English port and polities coalescing in the interior such as the Yamasees, Creeks, and Chickasaws. Slave raids by these groups radically altered the human landscape of the southeast in both creative and destructive ways. While some polities were driven to extinction from this violence, others migrated farther south and west, settling deep in the river deltas along the Gulf Coast and Mississippi River, where they clustered into multinational settlements for protection.

Relations with French Louisiana

When the French arrived on the Gulf Coast in 1699, they found a region reeling from the effects of the commercial Indian slave trade. The petites nations of the Biloxis, Mictobys, Bayagoulas, and Mougoulashas quickly incorporated the newcomers as refugee migrants, and permitted the French to build their first settlement, Fort Maurepas, near their towns located in present-day Ocean Springs, Mississippi. The alliance obligated the French honor regular renewals of the calumet, provide gifts and food to visiting Indian delegations, and conduct a steady trade in goods, especially firearms and cloth, to nearby towns. In exchange, the French received badly needed food, laborers, and assistance with diplomacy to large interior polities such as the Creeks, Choctaws, and Chickasaws. In 1702 the French accepted an invitation from the Mobilians, Naniabas (or Petit Tohomés), and the Grand Tohomés to relocate to the river delta north of present-day Mobile Bay. In 1704 Creek and Yamasee slave raids into Spanish Florida drove the Apalachees, Tawasas, and Chatots west to the multinational settlement gathering pace there. They were followed by the Taensas from the Mississippi River in 1713. By the 1720s ten petites nations towns totaling about seventeen hundred people resided near the French settlements of Mobile and Biloxi. Influenced by migrants from Spanish Florida, many of these petites nations adopted Christianity and housed priests in their towns.

The Chaouachas, Bayagoulas, Houmas, Acolopissas, Chitimachas, and Tunicas settled within a hundred miles of New Orleans and the other French settlements taking shape on the lower Mississippi River during the 1720s. Like in Mobile and Biloxi, these small nations provided much of the meat and produce consumed in these settlements. Other petites nations had a more complicated relationship with the French. The Yazoos, Tiouxs, Ofos/Ofogoulas, and Koroas at the Yazoo River multinational settlement site preferred alignment with the Natchez over migrating nearer the French. The Chitimachas initially welcomed the French with the calumet, but when a party of their warriors killed the Jesuit missionary Jean-François Buisson de Saint-Cosme and his companions in 1706, it sparked a devastating, twelve-year war and brought the colony some of its first enslaved Indian captives. Despite their claims to the contrary, the French participated in the Indian slave trade, often enslaving allies from among the petites nations.

Close contact with Europeans brought exposure to communicable diseases from which many petites nations people had no immunity, and within a few short years, most of those who had relocated north of Mobile, Biloxi, and New Orleans suffered catastrophic losses of seventy-to-ninety percent of their precontact populations. Those hardest hit merged with neighboring polities and ceased to appear in French records after the 1720s. Population losses from disease combined with chronic trade shortages strained relations between the colony and petites nations communities who demanded the French uphold their obligations as allies. When the French were unable to provide adequate trade or meet other expectations, petites nations people often refused to carry messages or supplies to inland posts or to broker deals with other Indigenous polities on behalf of the French or provide needed food. When the commercial Indian slave trade effectively ended after the Yamasee War (1715–1717), the balance of power in the region shifted beyond Europeans to favor the Chickasaws, Choctaws, Natchez, and Creeks. The petites nations forged multiple alliances with these polities, giving themselves leverage in dealings with Europeans. Having broad alliance networks offset small population sizes and equipped them to handle upcoming crises such as the Third Natchez War (1729–1730) and Choctaw Civil War (1746–1750). Petites nations cautiously chose sides in these conflicts or remained neutral depending on their unique and varied interests.

Life After the French

Under the 1762 Treaty of Fontainebleau Louisiana was secretly offered to Spain as a concession for their involvement in the Seven Years War as France’s ally. The 1763 Treaty of Paris yielded the eastern portion of Louisiana to Great Britain, ceding the western half to Spain. By the 1760s many petites nations had either merged with other polities like the Choctaws or disappeared outright. All were fractions of what they had been at the beginning of the century, but a few such as the Tunicas were rebounding and remained significant diplomatic players in the region despite having populations of approximately one hundred people. How they managed to survive speaks to their ingenuity and determination to reapply successful strategies from their past.

After 1763 most petites nations relocated to the eastern and western sides of the Mississippi River, which they frequently crossed to trade and hunt. Spain and Great Britain agreed to administer the inhabitants of their respective sides of the river. The petites nations used the ambiguity of their locations to play one empire against the other throughout the 1770s. Mutual fears between the thinly spread settler and soldier populations of Spanish Louisiana and British West Florida forced both colonies to engage with the different petites nations in the hopes of keeping them allies in the likely event another imperial contest occurred. Conflict with one of the principal interior Indigenous polities such as the Creeks also seemed likely. British and Spanish authorities, therefore, overlooked dual allegiances from petites nations leaders and granted them favorable trade concessions that shieled their communities from the uncertainty of the era.

Petites Nations Today

Struggles continued after the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. The push from American settler populations and the biracial Black and white caste system that developed during the nineteenth century complicated life for members of the petites nations in new ways. Although their communities avoided Indian Removal, they were still gradually dispossessed via land sales. Despite this, many petites nations families persisted and thrived alongside white people and African Americans as sharecroppers, trappers, and boatmen. During the early twentieth century, petites nations people began to organize for state and federal recognition. Historian Brian Klopotek has examined how the small populations of remaining petites nations communities were not, however, a budget priority for the underfunded Office of Federal Acknowledgment. Decades of intermarriage with white and African American neighbors further complicated the formal recognition process as many Jim Crow-era policymakers often considered these communities either too assimilated or too racially indistinct to warrant the right to become sovereign entities.

Decades-long campaigns for recognition joined with other civil rights causes during the mid-twentieth century with often uneven results. In Louisiana there are four federally recognized tribes—the Chitimacha, Coushatta, Tunica-Biloxi, and the Jena Band of Choctaw Indians—as well as eleven state-recognized tribes—the Natchitoches, Clifton Choctaw, Four Winds Cherokee, Jean Charles Choctaw Nation, Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi, Louisiana Band of Choctaw, Pointe-au Chien-Indian Tribe, Adai Caddo Indians of Louisiana, Choctaw-Apache Tribe of Ebarb, and Bayou Lafourche Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha Confederation of Muskogees—with members as descendants of the petites nations. Groups like the Chitimachas, Coushattas, Tunica-Biloxis, and Houmas among others retained their cultures and lifeways and exist today as a testament to their determination to survive. The names of rivers, parishes, counties, and cities across the Gulf Coast and lower Mississippi River valley also reflect the enduring legacy of the petites nations people to this day.