Latest

Reflecting on History in the Wake of George Floyd’s Killing

Reading for historical context

Published: June 3, 2020

Last Updated: June 3, 2020

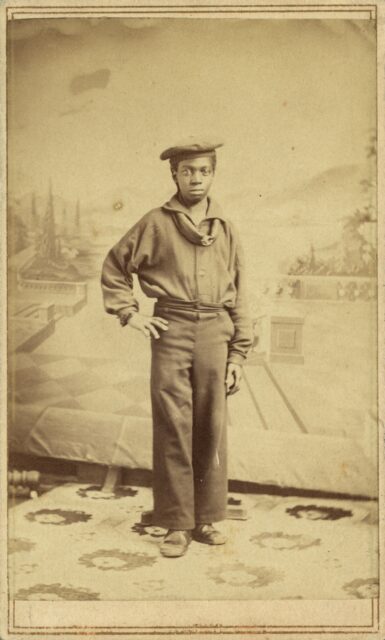

Courtesy of the Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans

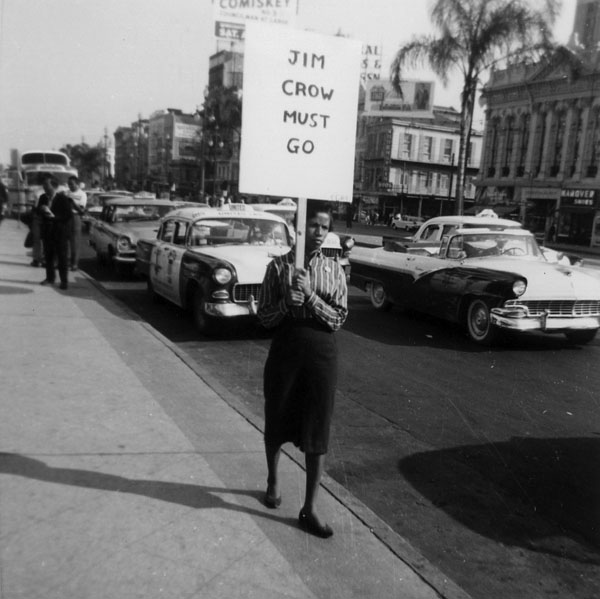

A black and white reproduction of a photograph of a New Orleans CORE protest at Woolworths and McCrory's on Canal Street, April 1961.

Under a makeshift flag bearing the Creole French “Morte ou librite” (death or liberty), reenactors storm the Bonnet Carre Spillway. Photo by Abdul Aziz

1. The German Coast Revolt of 1811: The denial of agency is a critical aspect of enslavement, but throughout history enslaved Africans and African Americans found ways to challenge the system that bound them. The German Coast Revolt of 1811, the largest uprising of enslaved people in American history, took place just upriver from New Orleans. Through collective and violent action, hundreds of enslaved people showed just how strong their desire for freedom was. The uprising, reenacted in November 2019, was one of several such insurrections that took place in pre-Emancipation Louisiana.

Not all challenges to America’s system of race-based, hereditary slavery were violent. Sometimes the enslaved ran away, facing myriad obstacles on their often unsuccessful roads to freedom. Some of their stories have been preserved in newspaper ads offering bounties for their recapture preserved by the Freedom on the Move project.

2. Sailing While Black: Possession of “free” status before Emancipation was no guarantee of freedom or even freedom of movement. Free black sailors, American or not, were perceived as dangerous in antebellum Louisiana and subjected to confinement or impressment while in port.

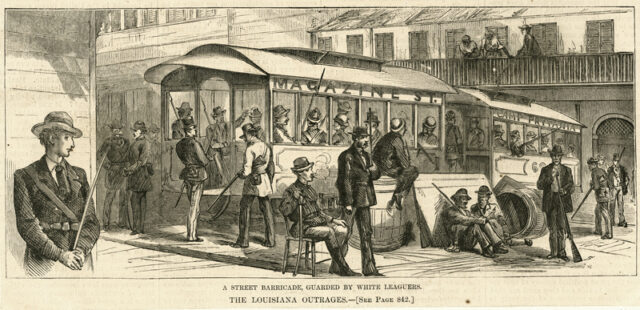

Reproduction of an illustration of A Street Barricaded, guarded by White Leaguers during the Battle of Liberty Place in New Orleans, 1874. Courtesy of the Historic New Orleans Collection

3. Resistance to Emancipation and Reconstruction: After the Confederacy’s surrender, resentments among Louisiana whites anxious to restore the pre-war order led to massacres of African Americans in Colfax in 1873 and Thibodaux in 1887 and of African Americans and white Republicans in Coushatta in 1874. Also in 1874, New Orleans saw the Battle of Liberty Place, a street battle between the Republican-dominated, integrated Metropolitan Police and the White League, a white supremacist organization that had also participated in the murders at Coushatta. The fighting left over thirty people dead, disarmed the black peacekeeping state militia force, and heavily reduced the power and authority of the state government, which was barely maintained by federal reinforcements. This “Redemption” of white power marked the beginning of the end of Reconstruction and its associated reform efforts. White League forces were notable for the number of Mardi Gras krewe members participating; a monument to the White League’s victory stood in New Orleans until 2017.

4. Segregation in Louisiana: Racial separation to the disadvantage of people of color was codified, primarily but not exclusively in the South, by “Jim Crow” laws passed in the late 19th century and upheld as constitutional by the United States Supreme Court in 1896’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision. Dismantling the legal framework of segregation has been a long process that remains incomplete. Boycott and civil disobedience efforts, like the Baton Rouge Bus Boycott of 1953, were key to setting up the legal challenges that began this process. Women have been especially prominent in civil rights work in Louisiana; activists like Oretha Castle Haley, Henrietta Windham Johnson, and Ruby Bridges are among the state’s leading Civil Rights–era figures.

Robert Penn Warren examined popular attitudes to segregation in his 1956 book Segregation: The Inner Conflict of the South, which collected his interviews with many southerners on either side of the color line, including himself. Writer Nathaniel Rich reread the text in 2016 and compared Penn’s findings with what he saw at contemporary political rallies.

In the late 1990s, Tom Dent wrote Southern Journey: A Return to the Civil Rights Movement (William Morrow & Company, 1997), reflecting on his own experiences growing up in segregated New Orleans and what he described as “a long, and very possibly insane, leisurely drive through the South over a period of several months,” recording conversations the Civil Rights Movement and its legacy of uneven progress. He shared an excerpt with 64 Parishes’ predecessor, Louisiana Cultural Vistas, shortly before his death.

The area under I-10 Claiborne Avenue was part of the largely African American Treme neighborhood. Photo by Christie Matherne Hall

5. Sacrificing Black Spaces: Black spaces have frequently been seen as expendable in the pursuit of larger goals. Mossville, a community in Calcasieu Parish founded by a freed slave in the late 18th century, suffered from widespread environmental pollution in the 20th and 21st centuries and was ultimately bought out by South African chemical manufacturer Sasol, forcing its residents off their ancestral lands. In 1964, Fazendeville, a black community in St. Bernard Parish, was cleared to make space for the historic National Park site dedicated to the Battle of New Orleans. And in New Orleans in the 1960s and 70s, the historic Treme neighborhood was bisected by the construction of I-10. In all of these cases, the homes, communities, and histories of African American were sacrificed for the profit or convenience of others.